N

Nathangun

Guest

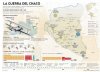

The Gran Chaco War: Fighting for Mirages in the Foothills of the Andes

The Gran Chaco is the most inhospitable part of the inhospitable Chaco Boreal, a largely uninhabited, 250,000 sq-mi region west of the Paraguay River and east of the foothills of the Andes in Paraguay, Bolivia, and Argentina. It is an arid, semi-desert, where some of the highest temperatures recorded in South America are encountered. In the west, near the mountains, the Gran Chaco is a flat, sparsely vegetated, waterless plain. Further east it is a thick, dry, almost impassable thornbrush jungle punctuated by dense stands of quebracho trees and grassy clearings. There are few people, but myriad biting, stinging insects and many tropical diseases. Prior to 1928, the region's only real value was the tannin extracted from its quebrachos and the meager grazing it provided for cattle. Such was the unlikely bone of contention in South America’s bloodiest, twentieth-century war.

The Gran Chaco belonged originally to the same Spanish colonial district (audiencia) as Bolivia. So it was, in Bolivian eyes, legally subject to the Spanish administration's successor government in La Paz. But the mountain peoples of the Bolivian Altiplano, a Quecha Indian underclass and a Spanish aristocracy, descended from Spanish conquistadores, had little real connection with the sweltering lowlands of the Gran Chaco or with the indigenous peoples who inhabited it. Bolivians did not live in the Chaco,nor did they exploit its meager resources. Bolivian businessmen looked into the possibility of a port on the Paraguay River, but otherwise did little to make use of the territory, gravely compromising their claims to the area, at least in North American and European eyes. On the other hand, the Guarani, the largely indigenous people of Paraguay, were linked to the Chaco by culture and language. Paraguayan settlers had long since brought cattle to the region and had established a tannin industry based on the quebracho. Paraguay had settled and improved the country. The government had brought industrious Mennonite communities from the United States to settle in the Chaco and had sold extensive tracts to Argentinian land developers and cattle companies. Thus, while Paraguay had claimed the Chaco when Spanish rule collapsed in 1810, its real hold rested on de facto grounds—use and occupation—rather than de jure title.

So matters might have rested. Bolivia might never have taken an interest in its one-time de jure territory, and Paraguay might have gone on with its quiet, unofficial settlements. But in 1884, Bolivia had lost the Pacific War and, with it her coastline, to Chile. To the nineteenth-century mind, great powers were sea powers that could carry on trade and project power over global distances. Suddenly, Bolivia had to either give up her aspirations to greatness or find some other outlet to the sea. The former course was anathema to fiercely nationalistic Bolivian politicians, newspaper editors, and student agitators. The officer corps of the defeated army likewise rejected any course that conceded the reality of defeat. Bolivians thus turned their hopes to their remaining frontier, the Chaco Boreal and its navigable border, the Paraguay River.

At first, both sides seemed content to press their claims by peaceful means. A series of international arbitrations and temporary settlements brokered by Argentina, President Hayes of the United States, and King Leopold of the Belgians kept the peace for a time. Both sides marshalled their historians and turned over their archives for supporting documentation. Meanwhile, the status quo continued.

Then, in 1928, oil was discovered in the foothills of the Andes at the western extremity of the Chaco. Bolivia suddenly took belated notice of its neglected territory and sought to assert its rights. The Gran Chaco seemed on the verge of an oil boom. Further oil fields might lie beneath the Chaco's arid plains. More importantly, Bolivian-controlled pipelines and a sovereign oil port now seemed absolutely necessary. Without them, Argentina would have a monopoly on shipping the oil and the nation's rightful profits would be syphoned off by foreign speculators. Paraguay reacted to this sudden onslaught from the north with violent indignation. The Guarani saw no reason why the late-comers from the mountains should enjoy the fruits of their labors, simply because a defunct colonial power had made a few thoughtless marks on a map. They were in no mood for territorial concessions. At the time of its independence from Spain in 1811, Paraguay had been one of the larger nations on the continent. But three neighbors, Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil, had seized more than half its territory in the War of the Triple Alliance. The loss still rankled, and impoverished Paraguay was not prepared to let its last hope for economic development join its other lost territories.

The Gran Chaco is the most inhospitable part of the inhospitable Chaco Boreal, a largely uninhabited, 250,000 sq-mi region west of the Paraguay River and east of the foothills of the Andes in Paraguay, Bolivia, and Argentina. It is an arid, semi-desert, where some of the highest temperatures recorded in South America are encountered. In the west, near the mountains, the Gran Chaco is a flat, sparsely vegetated, waterless plain. Further east it is a thick, dry, almost impassable thornbrush jungle punctuated by dense stands of quebracho trees and grassy clearings. There are few people, but myriad biting, stinging insects and many tropical diseases. Prior to 1928, the region's only real value was the tannin extracted from its quebrachos and the meager grazing it provided for cattle. Such was the unlikely bone of contention in South America’s bloodiest, twentieth-century war.

The Gran Chaco belonged originally to the same Spanish colonial district (audiencia) as Bolivia. So it was, in Bolivian eyes, legally subject to the Spanish administration's successor government in La Paz. But the mountain peoples of the Bolivian Altiplano, a Quecha Indian underclass and a Spanish aristocracy, descended from Spanish conquistadores, had little real connection with the sweltering lowlands of the Gran Chaco or with the indigenous peoples who inhabited it. Bolivians did not live in the Chaco,nor did they exploit its meager resources. Bolivian businessmen looked into the possibility of a port on the Paraguay River, but otherwise did little to make use of the territory, gravely compromising their claims to the area, at least in North American and European eyes. On the other hand, the Guarani, the largely indigenous people of Paraguay, were linked to the Chaco by culture and language. Paraguayan settlers had long since brought cattle to the region and had established a tannin industry based on the quebracho. Paraguay had settled and improved the country. The government had brought industrious Mennonite communities from the United States to settle in the Chaco and had sold extensive tracts to Argentinian land developers and cattle companies. Thus, while Paraguay had claimed the Chaco when Spanish rule collapsed in 1810, its real hold rested on de facto grounds—use and occupation—rather than de jure title.

So matters might have rested. Bolivia might never have taken an interest in its one-time de jure territory, and Paraguay might have gone on with its quiet, unofficial settlements. But in 1884, Bolivia had lost the Pacific War and, with it her coastline, to Chile. To the nineteenth-century mind, great powers were sea powers that could carry on trade and project power over global distances. Suddenly, Bolivia had to either give up her aspirations to greatness or find some other outlet to the sea. The former course was anathema to fiercely nationalistic Bolivian politicians, newspaper editors, and student agitators. The officer corps of the defeated army likewise rejected any course that conceded the reality of defeat. Bolivians thus turned their hopes to their remaining frontier, the Chaco Boreal and its navigable border, the Paraguay River.

At first, both sides seemed content to press their claims by peaceful means. A series of international arbitrations and temporary settlements brokered by Argentina, President Hayes of the United States, and King Leopold of the Belgians kept the peace for a time. Both sides marshalled their historians and turned over their archives for supporting documentation. Meanwhile, the status quo continued.

Then, in 1928, oil was discovered in the foothills of the Andes at the western extremity of the Chaco. Bolivia suddenly took belated notice of its neglected territory and sought to assert its rights. The Gran Chaco seemed on the verge of an oil boom. Further oil fields might lie beneath the Chaco's arid plains. More importantly, Bolivian-controlled pipelines and a sovereign oil port now seemed absolutely necessary. Without them, Argentina would have a monopoly on shipping the oil and the nation's rightful profits would be syphoned off by foreign speculators. Paraguay reacted to this sudden onslaught from the north with violent indignation. The Guarani saw no reason why the late-comers from the mountains should enjoy the fruits of their labors, simply because a defunct colonial power had made a few thoughtless marks on a map. They were in no mood for territorial concessions. At the time of its independence from Spain in 1811, Paraguay had been one of the larger nations on the continent. But three neighbors, Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil, had seized more than half its territory in the War of the Triple Alliance. The loss still rankled, and impoverished Paraguay was not prepared to let its last hope for economic development join its other lost territories.

Last edited by a moderator: