W

Wardog

Guest

I was pretty damn proud to be a loadmaster and flew in various situations, including Viet Nam. Did some heavy equipment, troops drops and medevac missions, too,

I joined the USAF as a 20 year old Canadian in October 1961, bored with the routine of city life and looking for some excitement.

I was first based at Lackland AFB in San Antonio, Texas for 8 weeks basic training, then I went on to Chanute AFB in Illinois for 16 weeks of training as a jet engine mechanic on the Pratt and Whitney J-57, used on the B-52.

Being from Canada I thought I had seen cold weather, but that winter in Southern Illinois was the coldest I had ever seen. The wind blew across those corn fields at 18 below F and chilled right down to the bone.

After training I was posted to Sewart AFB, Tennessee. However, working in the engine shop for one year was boring and was not what I really wanted from the Air Force. I was looking for adventure, so when an opportunity came up, I cross trained to be a loadmaster in Aug 1963, still at Sewart.

The base had 3 combat ready sqds. of C-130's and one training sqd for a total of 48 aircraft powered by Allison T-56-A7 turboprops, spinning a 14 foot four blade paddle prop. I spent a 60 day rotation at Clarke Air Base in the Phillippines. Our missions were in support of the Vietnam conflict. From there, we flew to Vietnam, Korea, Okinawa, Japan and Thailand. Bangkok was all that you may heard about. Really an eye opener. I never spent the night in Vietnam, but flew missions from base to base, then returned back to Okinawa.

One mission was particularly disconcerting. The first time we were approaching the Vietnam coastline, we intercepted a communication between a couple of fighter jockeys. One of their group had been hit by AA fire and was flying out over the ocean to eject rather on land where enemy forces might be. A wing man was accompanying the stricken aircraft and at the moment of ejection he called out "Safe ejection". But as he followed him down he kept calling out, "No chute". He called it all the way until he lost visibility in the haze at about 2000 ft. Last callout, was " No chute, no chute". It brought home the reality that we were entering a war zone and this was not a game.

Another time we were taking off at night from Bien Hoa, east of Saigon to fly back to Ton Sonhut in Saigon, about a 10 minute flight. Supposedly, Bien Hoa was a secured area, no enemy reported. However, as we lifted off in a maximum takeoff maneuver, tracer fire was passing by our nose. Secured area, oh yeah! No hits, luckily.

We did receive unknowingly, small arms ground fire once and it put a small hole in the belly of the aircraft and severed a wire causing an small electrical fire. We extinguished it and continued to our destination. We were not aware we'd been hit but while an electrician checked the wiring, he suddenly left the aircraft and crawled under the aircraft and found a small hole. Now we knew why the fire occurred.

On a mission from Okinawa to a landing zone in Vietnam, we were part of the first wave of aircraft that flew in thousands of marines to the Mecong Delta in 1965 over a three day period. As we were setting on final approach for landing on the dirt strip, about a mile or two on our right were A3D Skyraiders strafing and machining a mortar position the Viet Cong were setting up to start lobbing rounds onto the aircraft parked on the ground. It was quite a show. Apparently, the Skyraiders got them, because we had a successful landing and takeoff. We flew back to Okinawa, took a 'no go' pill and tried to sleep in a gymnasium full of double bunks with aircrew constantly coming and going. As soon as we were awake, we took a 'go' pill, load up the troops and made another flight back to the war zone. This went on for three days.

The loadmaster performs the calculations and plans cargo and passenger placement to keep the aircraft within permissible center of gravity limits throughout the flight.

Loadmasters ensure cargo is placed on the aircraft in such a way as to prevent overloading sensitive sections of the airframe and cargo floor.

Considerations are also given to civilian and military regulations which may prohibit the placement of one type of cargo in proximity to another.

Unusual cargo may require special equipment to be loaded safely aboard the aircraft, limiting where the other cargo may feasibly be placed.

The loadmaster may physically load the aircraft, but primarily supervises loading crews and procedures. Once positioned aboard the aircraft, the loadmaster ensures it is secured against movement.

Chains, straps, and integrated cargo locks are among the most common tools used to secure the cargo. Because the aircraft will execute abrupt maneuvers which may shift the cargo in flight, the loadmaster must determine the appropriate amount and placement of cargo restraint.

We used a special sliderule (no electronic calculators back in the 60's) to calculate the balance and the object was to get it around 30% MAC. (Mean aerodynamic chord).

But when we were fully loaded and grossed out 155,000 lbs we would try to load it to achieve 29%. A lot of pilots liked it a bit nose heavy since it was easier to

fly vs tail heavy.

As fuel burned off, the balance would move backward slightly. Of course, we had to know the exact weight of each piece of cargo so we could program it to specific locations called stations.

One of the heaviest loads I recall was a load of 750# bombs, without fuses or tail fins, chained to pallets which weighed in at some 34,000#, if I remember correctly.

We flew it across the Pacific from the Philippines to Japan.

With full fuel load we grossed out at over 167,000# which comprised of the basic aircraft weight, 69,800#, crew and baggage, 1500#, fuel load 62,000# and the balance was the load,

for a total of 167,300.

It felt like the bird would never get off the ground. We almost ran out of runway before the nose lifted. We couldn't climb to our assigned altitude of 24,000 ft. for about two hours until we burned off some fuel load.

We could over gross the airplane for takeoff to a max of 175,000# due to wartime conditions (VietNam), but could only land at 135,000#, so if we had to land over

that weight, we had to jetison fuel.

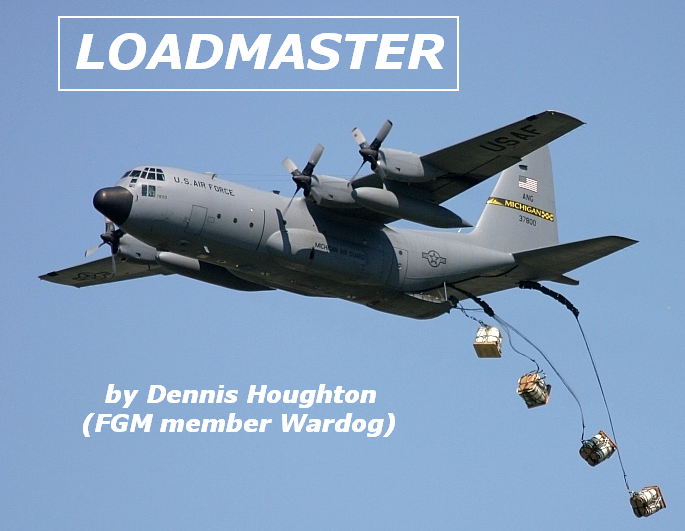

I was also qualified for "aerial delivery" of paratroops or cargo by parachute or ground proximity extraction, (no longer used due to the danger involved). Compared to the relatively routine transportation of cargo, airdrops can be a highly technical and dangerous undertaking.

Under some situations, the most effective way to resupply ground troops is by aerial delivery of equipment, ammunition, food, and medical supplies.

Many military victories have been dependent in large part upon aerial delivery.

In October 1965 I decided that I wanted to return to civilian life. Just after I was honorably discharged (after 4 years of service) my sqd, the 62nd TCS was transferred permanently to Okinawa and proceeded to be engaged regularly in Viet Nam.

Basic training memories, Lackland AFB, Texas 1961

Before being sworn in, we had to have a physical examination. The most amusing part of the day was the medical check for hemorrhoids and prostate gland problems. There were perhaps one hundred of us lining the corridor when the sergeant in charge ordered us to face the wall, drop our pants, bend over, and spread our cheeks. Doctors went from one guy to another, checking our tail holes.

There were a few loud farts which had us roaring in laughter until we where screamed at by a Sgt. "The next one that farts will get my size 12 brogan up their ass."

I was flown from New Jersey to San Antonio, Texas (home of Lackland AFB) on a shaky Lockheed Constellation.

It was my first flight ever. When we finally got to our destination at about 04:30, and got off the plane and boarded a bus. A tall, muscular sargeant from Louisiana sporting a pencil mustache and immaculately pressed fatigues with five stripes came aboard and began yelling at us in a menacing manner to get off the bus and fall in.

We staggered to our feet, tried to brush the sleep from our eyes, stumbled off the bus and fell into a rough semblance of a line. That's when it dawned on me that my life was about to be changed forever.

We had met our new Training Instructor, Technical Sgt. Bougois, a cajun from the bayous of southern Louisiana. He had a highly inflated sense of self-worth. His grammar suggested that he may have conquered the academic summits of grade school. His loud pronouncements established his intelligence as being slightly above that of a baboon. He had apparently received his present assignment because it called for little more than screaming at a bunch of kids fresh out of high school, attempting to intimidate them. And it worked, too.

He introduced to us our new life with ten or fifteen minutes of verbal abuse. He formed us into four lines, each containing about 15 men.

This was our "Flight." In the army it would have been called a platoon, but when the Air Force became a separate service, its founders apparently felt that their new force had to discard all remnants of its "brown shoe days," in favor of a new identity.

They created their own vocabulary, one designed to emphasize their new-found distinction. We weren't soldiers, we were "Airmen." Silly title. It sounds like something out of the junior birdman club for kids.

It became a lifetime of discipline crammed into 8 weeks of hell. In retrospect, not really all that bad and some of it was quite hilarious, as I see it now.

Anyone with military experience will be able to relate to this story. We were called rainbows because of the many different colors obviously with respect to our civil clothing.. When Tech Sgt. Bougois came on the scene, a new world was viewed and everyone was told the story that is forever ingrained in the minds of all involved: "I am your mother, your father, your brother, your sister, your girlfriend and even your pet dog! DO YOU HEAR ME, YOU SHITBIRDS?" Yes Sir! I DON'T HEEAR YOOU! YES SIR!

We were marched off for a lecture given by a young 2nd Lt. on the Uniform Code of Military Justice. He sat us down on the side of the road in a grassy and sandy patch.

Now if none of you have ever been to Texas then you probably wouldn't guess what comes next. I don't know if it was planned or not, but we were sitting on a bunch of fire ants nests.

If you don't know what a fire ant is, it's go a a bit that will burn like hell and produce a nasty blister. As we began to squirm, he pretended not to notice until someone asked if he could stand up.

"Of course, you can't stand". he said until he was finished with UCMJ. Basically, it stated that if we hit an officer or an NCO, off to the brig. We got through that session with a bunch of red welts on our asses.

Off to the barracks for bunk assignment. Our home for the next 8 weeks, Lackland Air Force Base was little more than a desert covered with concrete.

Our first day has began early. Several airmen were appointed "road guards" and they ran in front of the formation, waving flashlights at the intersections. It was still dark when we fell into formation and marched to the chow hall for our first breakfast. After breakfast, we formed up again, as we marched everywhere we went.

We were soon drawing uniforms and getting regulation haircuts.

At a huge, sprawling building nicknamed "the Green Monster," we were given batteries of tests to determine everything from mental health to job aptitudes. The latter rated our potential in four categories: electronics, mechanics, administrative and general.

The highest possible score was a 95. A counselor explained that our assignment would be based on (1) the needs of the Air Force, (2) our aptitudes, and (3) what we wanted, in that order.

We nervously awaited our assignments. The most apprehensive were the guys who failed to do well in the first three categories. If classified as "general" they would most likely end up as either an air policeman or a cook.

I scored well. I was destined to go into jet engine mechanics, just what I'd hoped for.

Each recruit was given 30 seconds or one minute (can't remember which) to get done with his shower. The first time it was pure mayhem. In Air Force basic training, there is no privacy for the showers. The shower is one large room, with several shower-heads. Everyone showers together.

For the first couple of weeks, you're being yelled at, even in the shower, so you don't worry about anything other than getting the shower finished as fast as you can.

After the first couple of weeks, when you get more time, and less yelling, it's no longer a big deal.

Lots of immunization shots. We shed our shirts, and slowly made our way down a very long line. At the end were medical corpsmen. We would would receive the air gun charge into the arm - a concoction of about 6 different ingredients at one time in each gun. Many guys collapsed, many more were so shaken that they staggered away, then sat down on the floor.

We were told to NOT MOVE when we got the shots. They had what looked like an air gun with a hose.

The vaccine was injected into each recruits arm under high pressure with this "gun". It burned like hell. If you made the mistake of moving, you could end up with a serious cut. We got a lot of shots!

Chowhall discipline required hands on your tray, sidestepping smartly. Take what you want BUT eat what you take!

Meals I remember that I liked breakfast the best. How can you mess up eggs and bacon? As for the other meals, there are a few things I HATED: Liver, Salisbury steak and SOS (shit on a shingle or creamed chipped beef on toast).

PT was a couple of hours morning and afternoon.

Running the obstacle course consumed a day. Swinging on a rope over a waterhole was the most troublesome for me. (I fell in twice). It should not have been hard, but drill instructors made everyone repeat it until they got across.

Many had earlier fallen into the mud hole and the result was a very slippery rope that was almost impossible to hold. Rappelling while explosive charges are going off all around you was interesting.

On to the Firing range. One day of dry fire, one day of live fire and qualifications. I had no problems qualifying. But when I began to put my zeroing rounds into the target, the guy next to me was missing his target completely (100 yards). It turned out that I was accidentally shooting at his target while I was zeroing my carbine. His weapon had been so far out he never hit his target. But since rounds had hit his target, I guess he figured he was spot on. My qualifying rounds went into my target and I qualified. Of course, when the poor guy next to me began to shoot his qualifying rounds they never even hit his target. Never did find out what happened to him.

He failed to qualify and had to repeat some courses, I guess. I never admitted it to anyone until basic was over.

I remember the obstacle course for the 1 mile run. One of the requirements for graduation was to run a mile under 9 minutes. I had never run a mile in my life.

My first attempt was over 9 minutes. I realized that I ran too fast in the beginning, and ran out of steam at the end. So I paced myself on the next attempt. This time I managed to make it under 9 minutes.

That was the last time I ever tried to run a mile. If I remember correctly, they gave you two or three chances to qualify on the mile run. If you didn't make it, they put you back to the next recruit class and nobody wanted to be put back for anything.

Mud crawl under barb wire while firing live rounds over out heads was scary. We were told not to stand up. Now who the hell would do that with live bullets zipping overhead.

And then there was KP.. Beside the required cleaning of the barracks and waxing the floors, I pulled KP two times ... Once I had to scrub and steam clean 35 gallon garbage cans behind the Chow Hall all day long.

The next time I ended up in pot and pans, scrubbing huge pots and pans ALL day long...12 hours of it These jobs were not the result of punishment. We all had to do some sort of work at one time or other. "Policing the area" was something the recruits did on a regular basis. It involved forming a long line, and then walking the area side-by-side looking for discarded cigarette butts and gum wrappers in the rain.

Those that didn't go to Sunday service ended up policing. The following Sunday the chapel was full of church goers.

Basic training was not what I expected. A lot of shoe shining, making beds so tight a dime would bounce and scrubbing the dorm floors until they sparkled. Learning to salute and drilling, drilling, drilling.

Graduation day...finally.

Now on to the the real Air Force.