In honor of the 80th anniversary of D-Day I would revive this thread.

These are from 2014 when my brothers and nephews took a grand six day tour of Normandy.

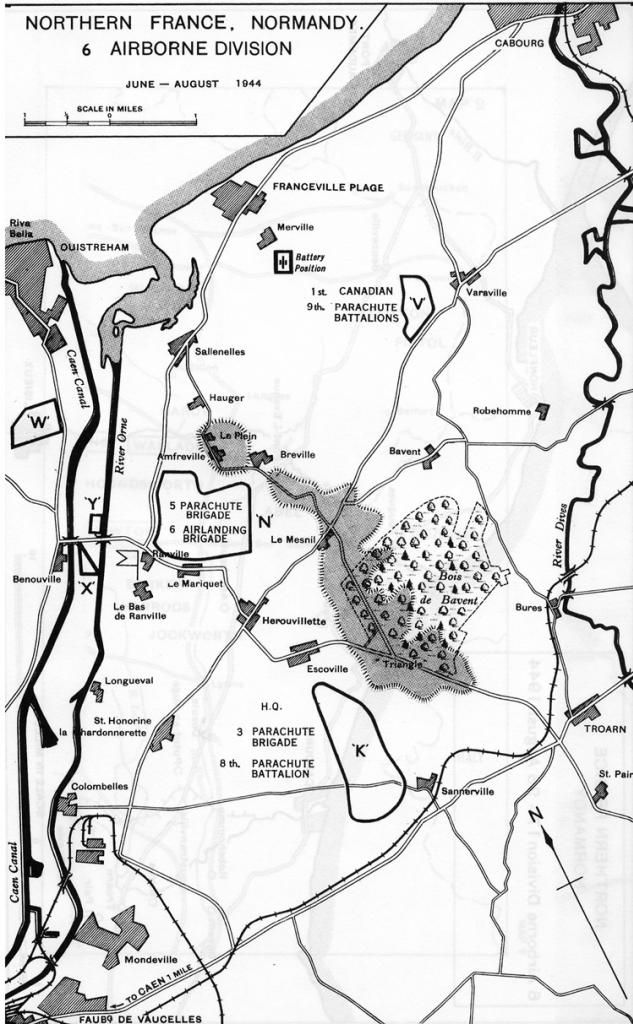

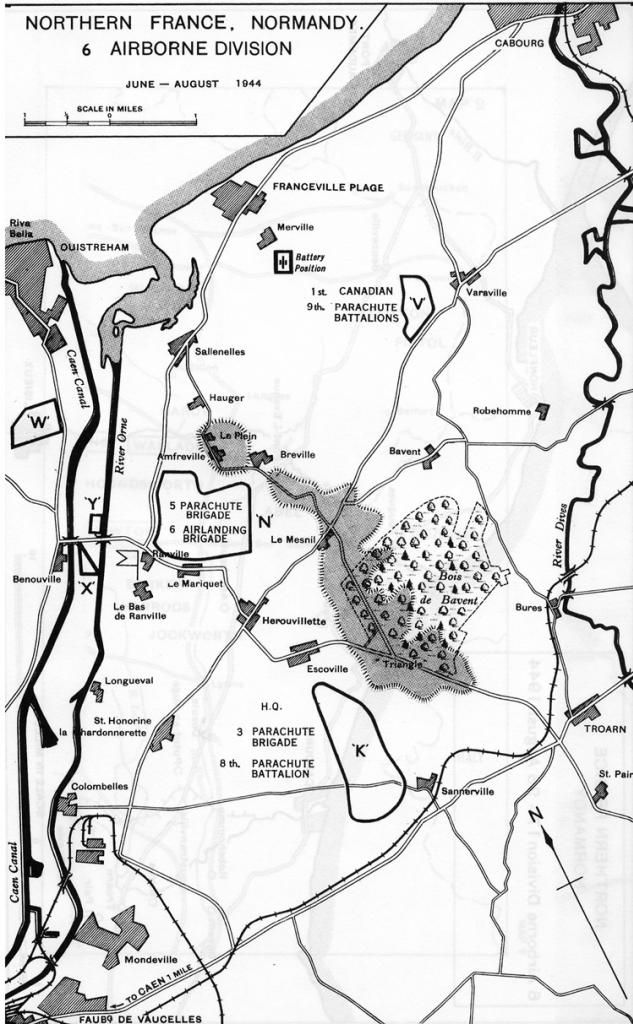

As the description says this was on the third day where we went out and followed the 6th Airborne

It's a little lengthy but I hope you enjoy the tour.

Hi and welcome to Day 3 of our tour.

This first post will be dedicated to Pegasus Bridge.

The itinerary for today:

Day 3 - British 6th Airborne Sector

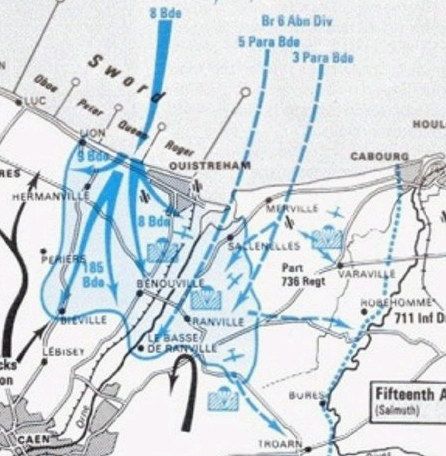

Pegasus Bridge - Major John Howard - 2nd Ox & Bucks Light Infantry in gliders - First action of D-Day

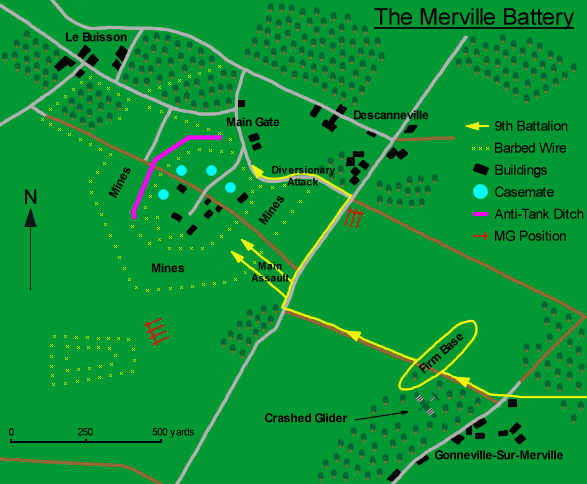

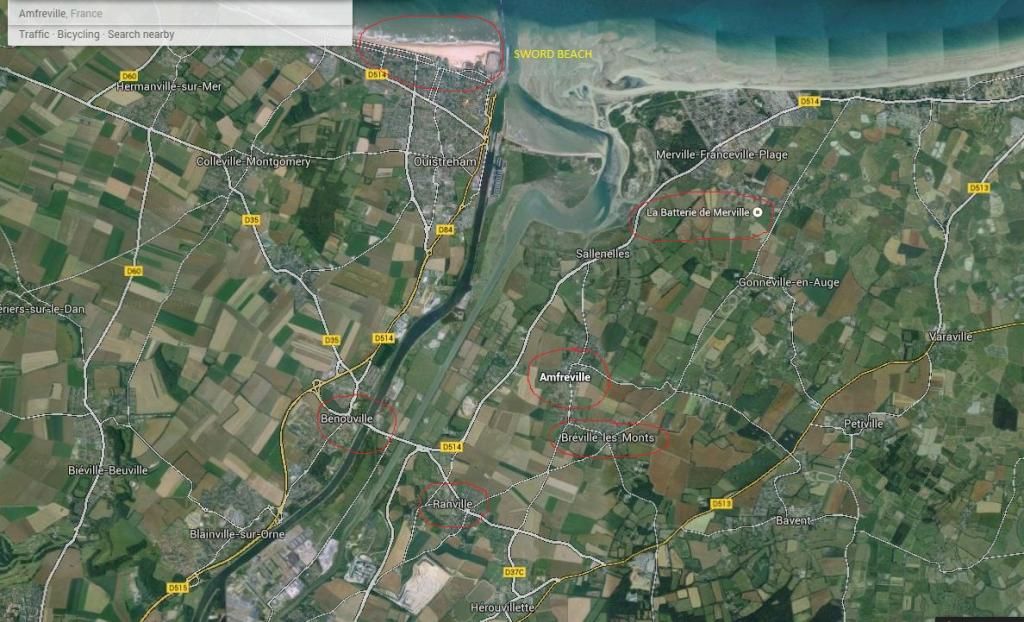

Merville Battery - 9 Para Bn - Lt Col Terrence Otway

Lunch - Café Gondrée - 1st House liberated - Mme Arlette Gondrée

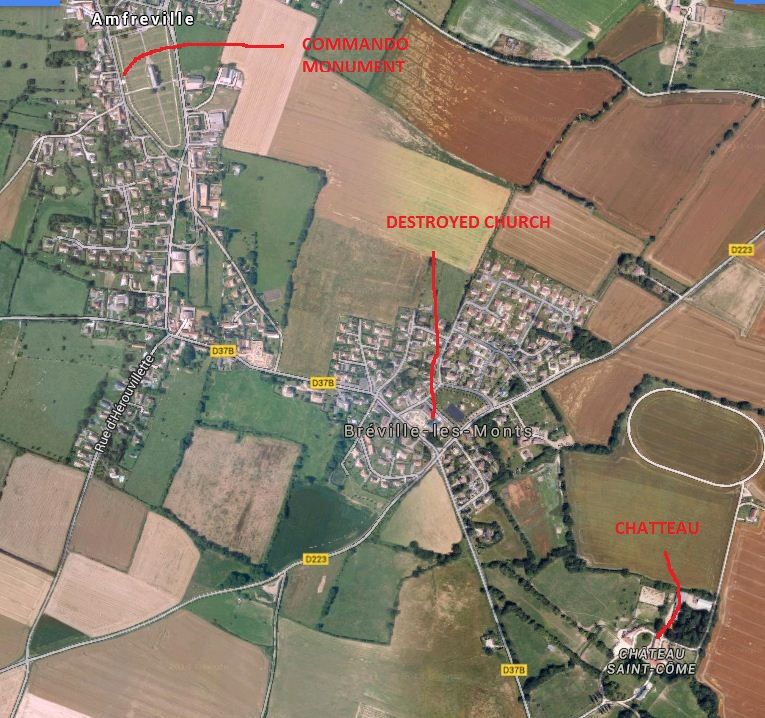

Amfreville - Commando and 6th Airborne positions - 1st memorials in Normandy

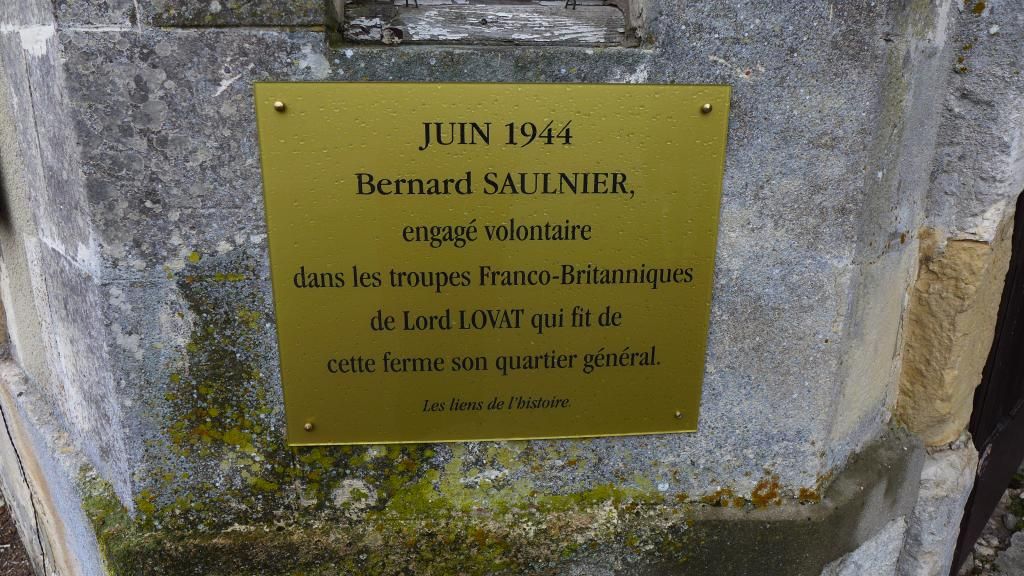

Le Plein - Madame Saulniers Farm used as aid station for British Commando units.

Breville - Church ruins

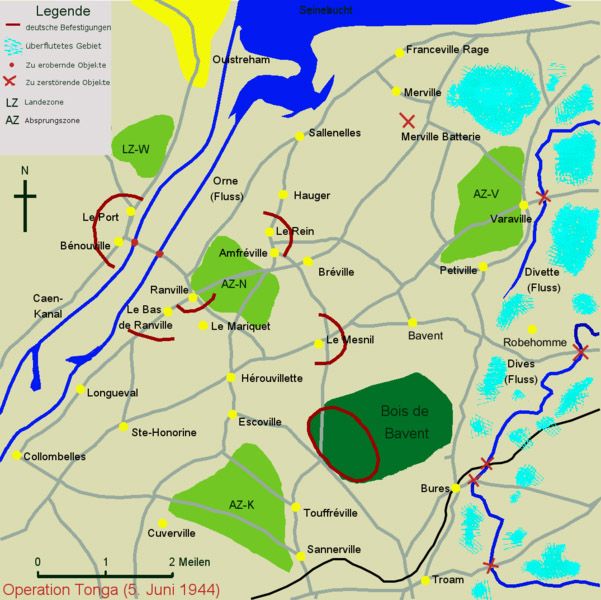

Breville Ridge - Drop Zone N (DZ-N)

Chateau St Come - 9 Para/1 Canadian Para/Black Watch/Ox & Bucks action

51st Highland Division Piper Memorial

Le Mesnil Crossroads

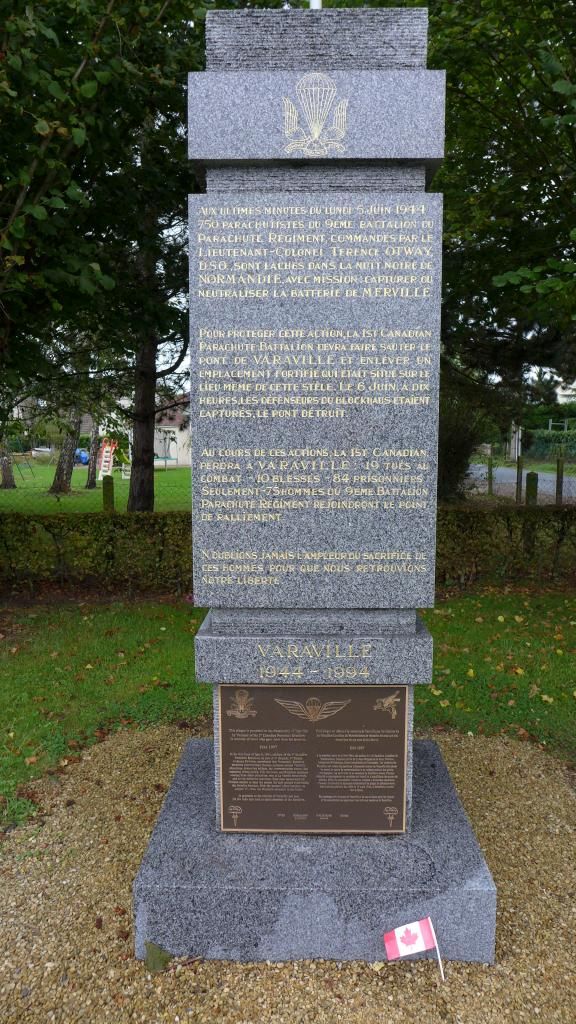

Varaville Bridge - Sgt Baillie

Varaville - Canadian 1st Para Battalion Memorial and Drop Zone V (DZ-V)

Robehomme Bridge - Lt Inman

Bures - Juckes Bridge - Capt Juckes

Bures - Railway Bridge - Lt Forster

Troarn Bridge - Major Roseveare

Of course when starting the British Airborne tour you have to start at Pegasus Bridge which most of you may know was the first action that took place on the night before the landings.

We parked in a museum parking lot down the street and started walking toward the bridge.

Man, it was pouring rain so I didn't have a chance to pull out the camera and take a lot of pictures.

Since there are few pictures I'm going to add some excerpts from David Howarth's excellent book "D-Day, the 6th of June" and a final paragraph from Wikipedia "Operation Dead Stick".

Major John Howard is in command.

On the other side of Howard, at the controls of the glider, was his pilot, Staff Sergeant Wallwork of the Glider Pilot Regiment, It was Wallwork who had done most to calm Howard's worries in the kst few weeks. For Howard, the whole three months of planning aud training had been a wonying time, and his worry had reached a climax on May 30th. On that day, he had been shown new aerial photographs of his bridges, and in all the fields round them, white spots could be seen which had not been there before. These, he was told, were holes for posts which were intended to make it impossible for gliders to land. The interpreters of photographs could not tell him whether posts had been put in the holes yet or not. Gloomily, he had shown the photographs to his pilots. They seemed delighted. "That's just what we needed/' Wallwork had said. "Well land between the posts. The posts will break the wings off and slow us down, and we shan't hit the bridge so hard."

It was impossible not to trust a pilot who could say a thing like that. Yet Howard, on his way across the Channel, was still wondering whether he had asked Wallwork and the others for something impossible. He had told them he wanted the first glider to stop with its nose inside the wire defenses of the bridge, and the others to stop ten yards behind and five yards to the right. He had no idea how such precision could be achieved, but they had made light of it, and his troops had caught their mood of confidence.

……

"Hold tight/' Wallwork said; and all the platoon linked arms and lifted their feet off the floor and sat there locked together, waiting.

The concussion was shattering. The glider tore into the earth at ninety miles an hour, and careened across the tiny field with a noise like thunder as timber cracked and split and it smashed itself to pieces. The stunning noise and shocks went on and on for a count of seconds; and then suddenly for a split second everything was perfectly still and silent. But even in the stunned silence, training worked. Howard found he had undone his belt and was on his feet. The doorway had crumpled into wreckage. But in front of him was a jagged hole in the glider's side and he went through it head first and fell on the earth of France, picked himself up and felt his limbs for broken bones and looked up; and there against the night sky, exactly and precisely where it should have been, twenty paces away, was the steel lattice tower of the bridge. Brotheridge came running round the tail: he had got out of a hole on the other side. "All right?" he said "Yes/' Howard said. "Carry on/' Brotheridge shouted his pktoon letter, "Able, Able," to rally the men who were tumbling out of the wreckage, and the action began which they had rehearsed on bridges all over England A phosphorus smoke bomb was thrown at the pillbox by the bridge. A machine gun opened fire from it, but one man ran forward under cover of the smoke and dropped a Mills bomb through the gun port, and the platoon scrambled across the wire which the glider had demolished, up an embankment onto the road, and with yells of "Able, Able" they dashed across the bridge against the fire of a second machine gun on the far side. Howard made for the spot he had named as his command post, followed by his radio operator, Corporal Tappenden, and as he ran he heard a crash behind him, and then another; the other two gliders coming in. Soon above the noise of small-arms fire he heard his second and third platoons come miming through the darkness, shouting "Baker" and "Charlie," not only to identify themselves, but also because men shout by instinct when they charge into a battle.

…..

The sentry on the bridge was a young German called Helmut Romer, and when he saw the first glider crash he naturally thought it was a bomber, because there were heavy air-raids going on in Caen and along the coast, and he had been watching the antiaircraft fire. Nobody had told him anything more than an air-raid was expected. So when men with black faces charged across the bridge at him, he was totally taken by surprise. He dived for the trenches: it was the only thing he could do. There was no time for the guard to turn out, much less for the whole platoon to be called from their billets. But the NCO of the guard fired the machine gun and shot down the first of the men who were coming across the bridge. Then the wave of them broke into the trenches, and the garrison scattered and ran.

Within three minutes of the crash, the attack had succeeded. Engineers searched for the demolition wiring and disconnected it. The charge itself had not been put in place. They found it afterwards in a cache by the bridgehead. With the bridge in their hands, the infantry went on to clear out the houses beyond it.

....

The attack on the Orne bridge had been a walk-over. The landing had not been so precise as the landing at the canal. One glider was close to the bridge, but the next was a quarter of a mile away. The third was cast off from its tug in the wrong place, and landed beyond the marshes of the Dives. Even the first of the three was a minute or two behind the first at the canal, and the leading platoon, commanded by Lieutenant Fox, got to the bridge just in time to see the German defenders running for their lives. One of Fox's NCOs jumped into an empty machine-gun post and turned the German gun against the retreating Germans; and his commander of the second platoon, running breathlessly onto the bridge some minutes late, found Fox in the middle of it, staring down at the dark water of the Orne. "How's it gone?" he asked anxiously. "It's gone all right," Fox said. "But where the hell are the umpires?"

The code words which Howard had been allotted to signal the success of his attack had none of the air of modest triumph which might have suited the very first success of the invasion. The capture of the canal bridge intact was to be reported by radio to brigade headquarters by the word "ham." For the Orne bridge the word was "jam." Corporal

Tappenden could not get an acknowledgment from brigade, and for half an hour, squatting by the roadside, he broadcast those pregnant words: "Ham and jam. Ham and jam. Ham and jam." Meanwhile, the six platoons, weakened now by the losses of the crash and the fighting, attended their dead and wounded and prepared to defend what they had won; for a counterattack was expected as soon as the Germans had recovered from their surprise, and until Howard's men could be reinforced by the main body of the parachutists, they were in a perilous position.

.........

Just before dawn Howard summoned his platoon commanders to a meeting. With their senior officers dead or wounded, numbers One, Two and Three Platoons were now commanded by corporals. Howard's second in command, Captain Priday and number Four Platoon were missing. Only Lieutenants Fox and Sweeney in Five and Six Platoons had a full complement of officers and NCOs. The landings at Sword Beach began at 07:00, preceded by a heavy naval bombardment. At the bridges, daylight allowed German snipers to identify targets and anyone moving in the open was in danger of being shot. The men of number One Platoon who had taken over the 75 mm anti-tank gun on the east bank of the canal used it to engage possible sniper positions in Bénouville, the Château de Bénouville and the surrounding area. At 09:00, two German gunboats approached the canal bridge from Ouistreham. The lead boat fired its 20 mm gun and number Two Platoon returned fire with a PIAT, hitting the wheelhouse of the leading boat, which crashed into the canal bank. The second boat retreated to Ouistreham. A lone German aircraft bombed the canal bridge at 10:00, dropping one bomb. The bomb struck the bridge but failed to detonate.

Aftermath

Bénouville was the farthest forward point of the British advance on 6 June 1944.[88] Of the 181 men (139 infantry, 30 engineers and 12 pilots) of 'D' Company involved in the capture of the bridges, two had been killed and fourteen wounded. On 9 June, the German Air Force attacked the bridges with 13 aircraft. The British had positioned light and medium sized anti-aircraft guns around the bridges and in the face of intense anti-aircraft fire the attack failed, although they did claim one of the bridges was destroyed by a direct hit.

The 6th Airborne retained control of the area between the Rivers Orne and Dives until 14 June, when the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division took over the southern part of the Orne bridgehead. In the days that followed the division was reinforced by the Dutch Princess Irene Brigade and the 1st Belgian Infantry Brigade. A period of static warfare ended on 22 August when the division crossed the River Dives. Within nine days it had advanced 45 miles (72 km) to the mouth of the River Seine. Between the 6 June and 26 August when they were pulled out of the front line the division's casualties were; 821 killed, 2,709 wounded, and 927 missing. After Operation Deadstick the engineers, glider pilots and 'B' Company men were returned to their parent formations. 'D' Company played their part in the division's defence of the Orne bridgehead and advance to the River Seine. On 5 September when the division was withdrawn to England, all that remained of the company were 40 men under the only remaining officer, Howard, the other officers, sergeants and most of the junior NCOs having been among the casualties.

The glider pilots were the first group to leave 'D' Company, their expertise being required for other planned operations. In particular Operation Comet, which included another coup-de-main operation where eighteen gliders would be used to capture three bridges in the Netherlands. The mission would be carried out by the 1st Airborne Division with a brigade allocated to defend each bridge. Comet was scheduled for the 8 September 1944, but was delayed and then cancelled. The plans were adapted and became Operation Market Garden, involving three airborne divisions, however the coup-de-main assault plans were not carried out.

Prior to being withdrawn on 16 July, Howard was awarded the Distinguished Service Order, presented in the field by General Bernard Montgomery. Other awards were the Military Cross to Smith and Sweeney,[93][94] the Military Medal to Sergeant Thornton and Lance-Corporal Stacey, Lieutenant Brotheridge was posthumously mentioned in dispatches. Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory of the Royal Air Force praised the pilots involved, saying the operation included the "most outstanding flying achievements of the war". The feat was recognised by the award of the Distinguished Flying Medal to eight of the glider pilots involved.

Walking toward the bridge from the parking lot.

A view from next to the 75mm gun Howard's men used point towards Benouville.

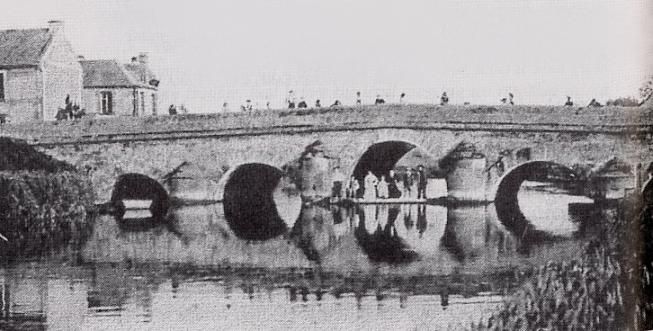

What it looked like then:

(Notice the small building on the right,. That's the Cafe Gondree where we had lunch. We met the proprietor, the daughter of the original owner, is a very nice elderly lady was just a little girl at the time of the invasion)

Cafe Gondree:

(The place is filled with memorabilia but no pictures are allowed to be taken inside.)

A shot of the original bridge preserved at the museum where we parked:

A view from the opposite bank:

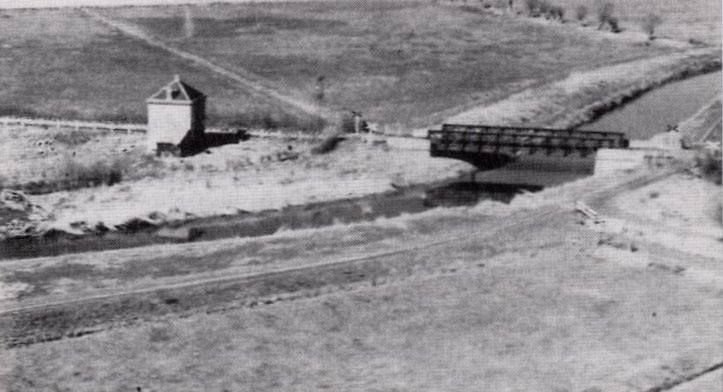

An aerial shot taken shortly after D-Day.

The bridge is in the lower left. You can see the circular gun emplacement.

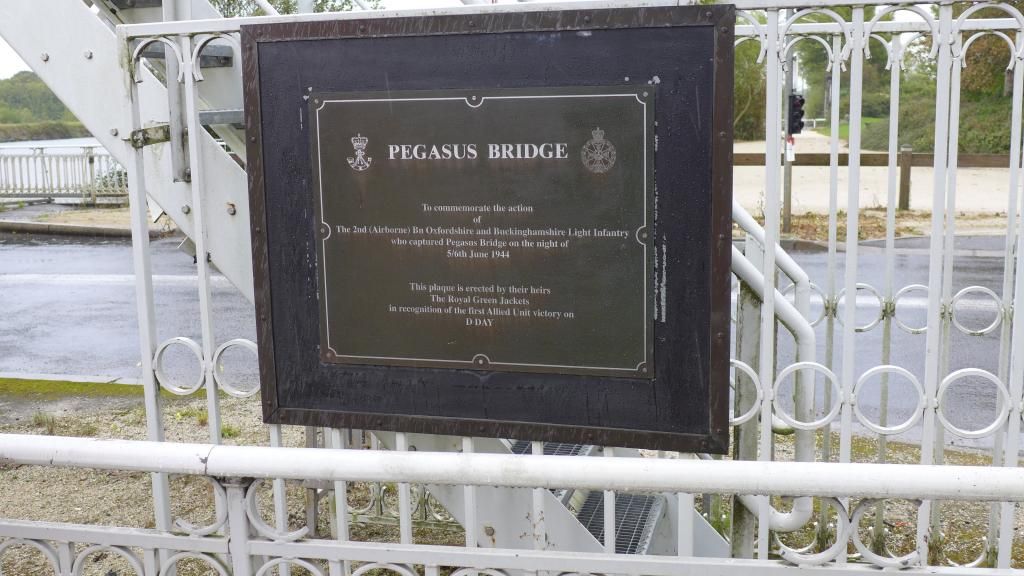

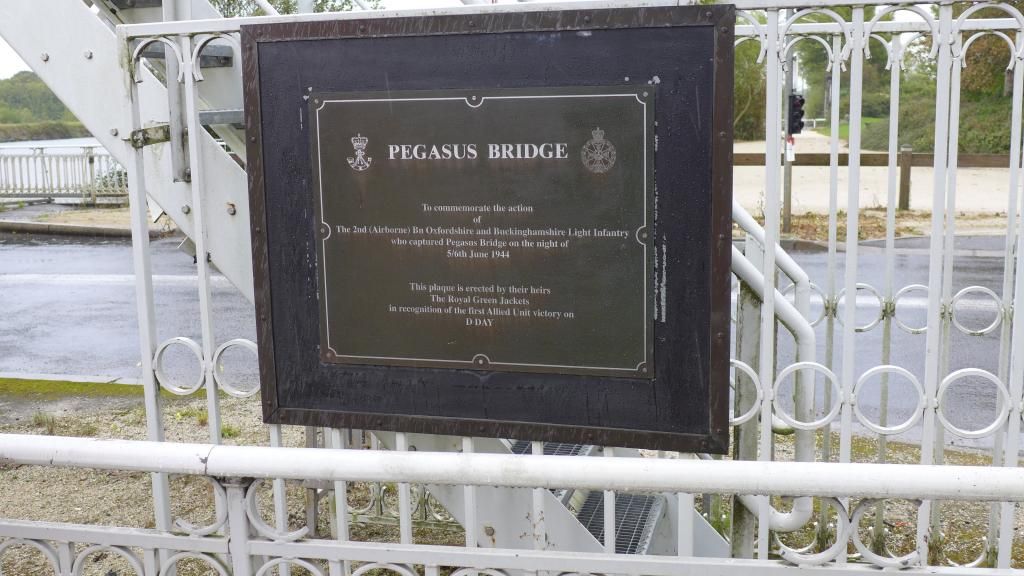

The plaque commemorating the landing:

A final note.

If you watch "The Longest Day" the attack on the bridge is filmed here on location.

These are from 2014 when my brothers and nephews took a grand six day tour of Normandy.

As the description says this was on the third day where we went out and followed the 6th Airborne

It's a little lengthy but I hope you enjoy the tour.

Hi and welcome to Day 3 of our tour.

This first post will be dedicated to Pegasus Bridge.

The itinerary for today:

Day 3 - British 6th Airborne Sector

Pegasus Bridge - Major John Howard - 2nd Ox & Bucks Light Infantry in gliders - First action of D-Day

Merville Battery - 9 Para Bn - Lt Col Terrence Otway

Lunch - Café Gondrée - 1st House liberated - Mme Arlette Gondrée

Amfreville - Commando and 6th Airborne positions - 1st memorials in Normandy

Le Plein - Madame Saulniers Farm used as aid station for British Commando units.

Breville - Church ruins

Breville Ridge - Drop Zone N (DZ-N)

Chateau St Come - 9 Para/1 Canadian Para/Black Watch/Ox & Bucks action

51st Highland Division Piper Memorial

Le Mesnil Crossroads

Varaville Bridge - Sgt Baillie

Varaville - Canadian 1st Para Battalion Memorial and Drop Zone V (DZ-V)

Robehomme Bridge - Lt Inman

Bures - Juckes Bridge - Capt Juckes

Bures - Railway Bridge - Lt Forster

Troarn Bridge - Major Roseveare

Of course when starting the British Airborne tour you have to start at Pegasus Bridge which most of you may know was the first action that took place on the night before the landings.

We parked in a museum parking lot down the street and started walking toward the bridge.

Man, it was pouring rain so I didn't have a chance to pull out the camera and take a lot of pictures.

Since there are few pictures I'm going to add some excerpts from David Howarth's excellent book "D-Day, the 6th of June" and a final paragraph from Wikipedia "Operation Dead Stick".

Major John Howard is in command.

On the other side of Howard, at the controls of the glider, was his pilot, Staff Sergeant Wallwork of the Glider Pilot Regiment, It was Wallwork who had done most to calm Howard's worries in the kst few weeks. For Howard, the whole three months of planning aud training had been a wonying time, and his worry had reached a climax on May 30th. On that day, he had been shown new aerial photographs of his bridges, and in all the fields round them, white spots could be seen which had not been there before. These, he was told, were holes for posts which were intended to make it impossible for gliders to land. The interpreters of photographs could not tell him whether posts had been put in the holes yet or not. Gloomily, he had shown the photographs to his pilots. They seemed delighted. "That's just what we needed/' Wallwork had said. "Well land between the posts. The posts will break the wings off and slow us down, and we shan't hit the bridge so hard."

It was impossible not to trust a pilot who could say a thing like that. Yet Howard, on his way across the Channel, was still wondering whether he had asked Wallwork and the others for something impossible. He had told them he wanted the first glider to stop with its nose inside the wire defenses of the bridge, and the others to stop ten yards behind and five yards to the right. He had no idea how such precision could be achieved, but they had made light of it, and his troops had caught their mood of confidence.

……

"Hold tight/' Wallwork said; and all the platoon linked arms and lifted their feet off the floor and sat there locked together, waiting.

The concussion was shattering. The glider tore into the earth at ninety miles an hour, and careened across the tiny field with a noise like thunder as timber cracked and split and it smashed itself to pieces. The stunning noise and shocks went on and on for a count of seconds; and then suddenly for a split second everything was perfectly still and silent. But even in the stunned silence, training worked. Howard found he had undone his belt and was on his feet. The doorway had crumpled into wreckage. But in front of him was a jagged hole in the glider's side and he went through it head first and fell on the earth of France, picked himself up and felt his limbs for broken bones and looked up; and there against the night sky, exactly and precisely where it should have been, twenty paces away, was the steel lattice tower of the bridge. Brotheridge came running round the tail: he had got out of a hole on the other side. "All right?" he said "Yes/' Howard said. "Carry on/' Brotheridge shouted his pktoon letter, "Able, Able," to rally the men who were tumbling out of the wreckage, and the action began which they had rehearsed on bridges all over England A phosphorus smoke bomb was thrown at the pillbox by the bridge. A machine gun opened fire from it, but one man ran forward under cover of the smoke and dropped a Mills bomb through the gun port, and the platoon scrambled across the wire which the glider had demolished, up an embankment onto the road, and with yells of "Able, Able" they dashed across the bridge against the fire of a second machine gun on the far side. Howard made for the spot he had named as his command post, followed by his radio operator, Corporal Tappenden, and as he ran he heard a crash behind him, and then another; the other two gliders coming in. Soon above the noise of small-arms fire he heard his second and third platoons come miming through the darkness, shouting "Baker" and "Charlie," not only to identify themselves, but also because men shout by instinct when they charge into a battle.

…..

The sentry on the bridge was a young German called Helmut Romer, and when he saw the first glider crash he naturally thought it was a bomber, because there were heavy air-raids going on in Caen and along the coast, and he had been watching the antiaircraft fire. Nobody had told him anything more than an air-raid was expected. So when men with black faces charged across the bridge at him, he was totally taken by surprise. He dived for the trenches: it was the only thing he could do. There was no time for the guard to turn out, much less for the whole platoon to be called from their billets. But the NCO of the guard fired the machine gun and shot down the first of the men who were coming across the bridge. Then the wave of them broke into the trenches, and the garrison scattered and ran.

Within three minutes of the crash, the attack had succeeded. Engineers searched for the demolition wiring and disconnected it. The charge itself had not been put in place. They found it afterwards in a cache by the bridgehead. With the bridge in their hands, the infantry went on to clear out the houses beyond it.

....

The attack on the Orne bridge had been a walk-over. The landing had not been so precise as the landing at the canal. One glider was close to the bridge, but the next was a quarter of a mile away. The third was cast off from its tug in the wrong place, and landed beyond the marshes of the Dives. Even the first of the three was a minute or two behind the first at the canal, and the leading platoon, commanded by Lieutenant Fox, got to the bridge just in time to see the German defenders running for their lives. One of Fox's NCOs jumped into an empty machine-gun post and turned the German gun against the retreating Germans; and his commander of the second platoon, running breathlessly onto the bridge some minutes late, found Fox in the middle of it, staring down at the dark water of the Orne. "How's it gone?" he asked anxiously. "It's gone all right," Fox said. "But where the hell are the umpires?"

The code words which Howard had been allotted to signal the success of his attack had none of the air of modest triumph which might have suited the very first success of the invasion. The capture of the canal bridge intact was to be reported by radio to brigade headquarters by the word "ham." For the Orne bridge the word was "jam." Corporal

Tappenden could not get an acknowledgment from brigade, and for half an hour, squatting by the roadside, he broadcast those pregnant words: "Ham and jam. Ham and jam. Ham and jam." Meanwhile, the six platoons, weakened now by the losses of the crash and the fighting, attended their dead and wounded and prepared to defend what they had won; for a counterattack was expected as soon as the Germans had recovered from their surprise, and until Howard's men could be reinforced by the main body of the parachutists, they were in a perilous position.

.........

Just before dawn Howard summoned his platoon commanders to a meeting. With their senior officers dead or wounded, numbers One, Two and Three Platoons were now commanded by corporals. Howard's second in command, Captain Priday and number Four Platoon were missing. Only Lieutenants Fox and Sweeney in Five and Six Platoons had a full complement of officers and NCOs. The landings at Sword Beach began at 07:00, preceded by a heavy naval bombardment. At the bridges, daylight allowed German snipers to identify targets and anyone moving in the open was in danger of being shot. The men of number One Platoon who had taken over the 75 mm anti-tank gun on the east bank of the canal used it to engage possible sniper positions in Bénouville, the Château de Bénouville and the surrounding area. At 09:00, two German gunboats approached the canal bridge from Ouistreham. The lead boat fired its 20 mm gun and number Two Platoon returned fire with a PIAT, hitting the wheelhouse of the leading boat, which crashed into the canal bank. The second boat retreated to Ouistreham. A lone German aircraft bombed the canal bridge at 10:00, dropping one bomb. The bomb struck the bridge but failed to detonate.

Aftermath

Bénouville was the farthest forward point of the British advance on 6 June 1944.[88] Of the 181 men (139 infantry, 30 engineers and 12 pilots) of 'D' Company involved in the capture of the bridges, two had been killed and fourteen wounded. On 9 June, the German Air Force attacked the bridges with 13 aircraft. The British had positioned light and medium sized anti-aircraft guns around the bridges and in the face of intense anti-aircraft fire the attack failed, although they did claim one of the bridges was destroyed by a direct hit.

The 6th Airborne retained control of the area between the Rivers Orne and Dives until 14 June, when the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division took over the southern part of the Orne bridgehead. In the days that followed the division was reinforced by the Dutch Princess Irene Brigade and the 1st Belgian Infantry Brigade. A period of static warfare ended on 22 August when the division crossed the River Dives. Within nine days it had advanced 45 miles (72 km) to the mouth of the River Seine. Between the 6 June and 26 August when they were pulled out of the front line the division's casualties were; 821 killed, 2,709 wounded, and 927 missing. After Operation Deadstick the engineers, glider pilots and 'B' Company men were returned to their parent formations. 'D' Company played their part in the division's defence of the Orne bridgehead and advance to the River Seine. On 5 September when the division was withdrawn to England, all that remained of the company were 40 men under the only remaining officer, Howard, the other officers, sergeants and most of the junior NCOs having been among the casualties.

The glider pilots were the first group to leave 'D' Company, their expertise being required for other planned operations. In particular Operation Comet, which included another coup-de-main operation where eighteen gliders would be used to capture three bridges in the Netherlands. The mission would be carried out by the 1st Airborne Division with a brigade allocated to defend each bridge. Comet was scheduled for the 8 September 1944, but was delayed and then cancelled. The plans were adapted and became Operation Market Garden, involving three airborne divisions, however the coup-de-main assault plans were not carried out.

Prior to being withdrawn on 16 July, Howard was awarded the Distinguished Service Order, presented in the field by General Bernard Montgomery. Other awards were the Military Cross to Smith and Sweeney,[93][94] the Military Medal to Sergeant Thornton and Lance-Corporal Stacey, Lieutenant Brotheridge was posthumously mentioned in dispatches. Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory of the Royal Air Force praised the pilots involved, saying the operation included the "most outstanding flying achievements of the war". The feat was recognised by the award of the Distinguished Flying Medal to eight of the glider pilots involved.

Walking toward the bridge from the parking lot.

A view from next to the 75mm gun Howard's men used point towards Benouville.

What it looked like then:

(Notice the small building on the right,. That's the Cafe Gondree where we had lunch. We met the proprietor, the daughter of the original owner, is a very nice elderly lady was just a little girl at the time of the invasion)

Cafe Gondree:

(The place is filled with memorabilia but no pictures are allowed to be taken inside.)

A shot of the original bridge preserved at the museum where we parked:

A view from the opposite bank:

An aerial shot taken shortly after D-Day.

The bridge is in the lower left. You can see the circular gun emplacement.

The plaque commemorating the landing:

A final note.

If you watch "The Longest Day" the attack on the bridge is filmed here on location.

Last edited: