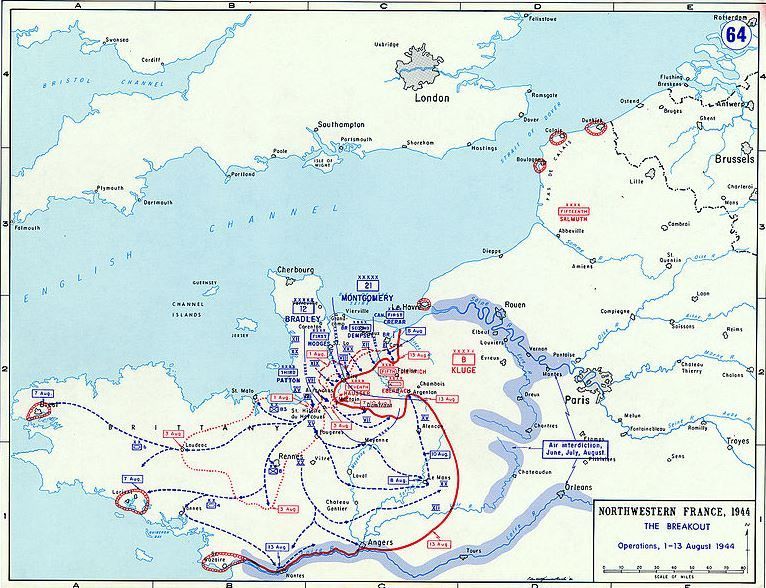

2) The story

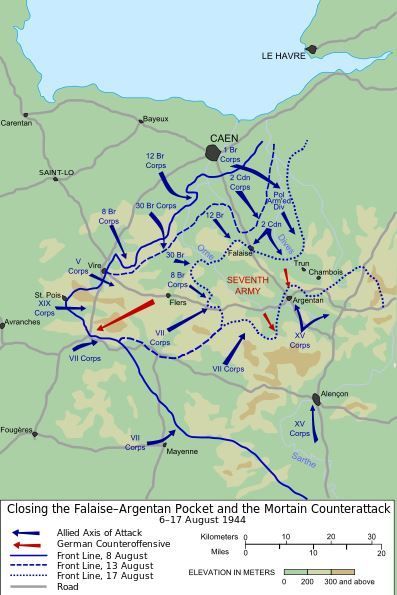

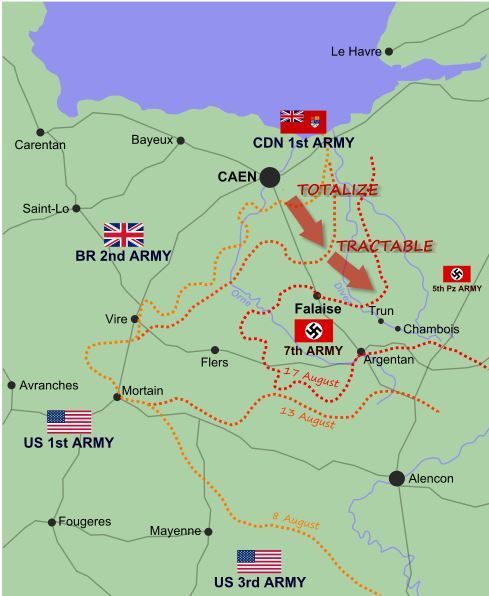

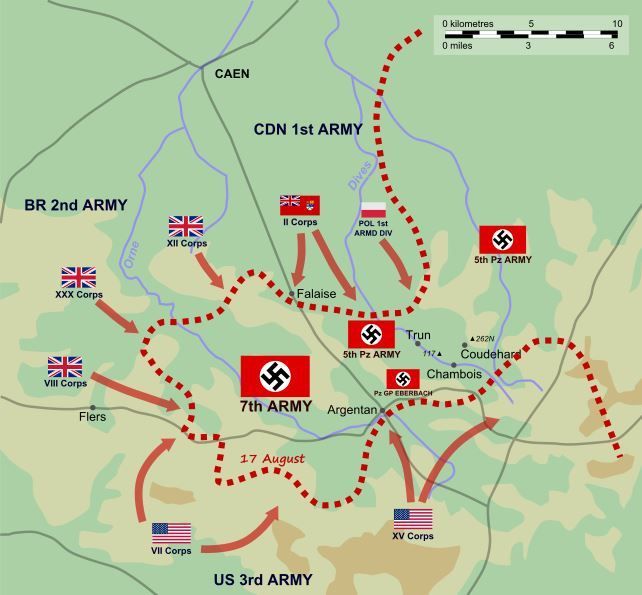

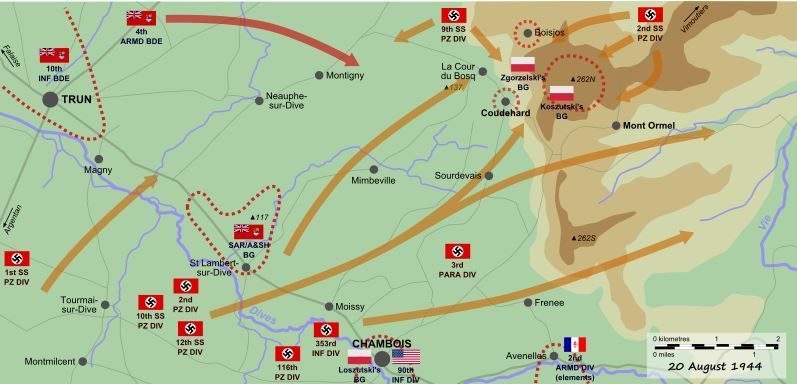

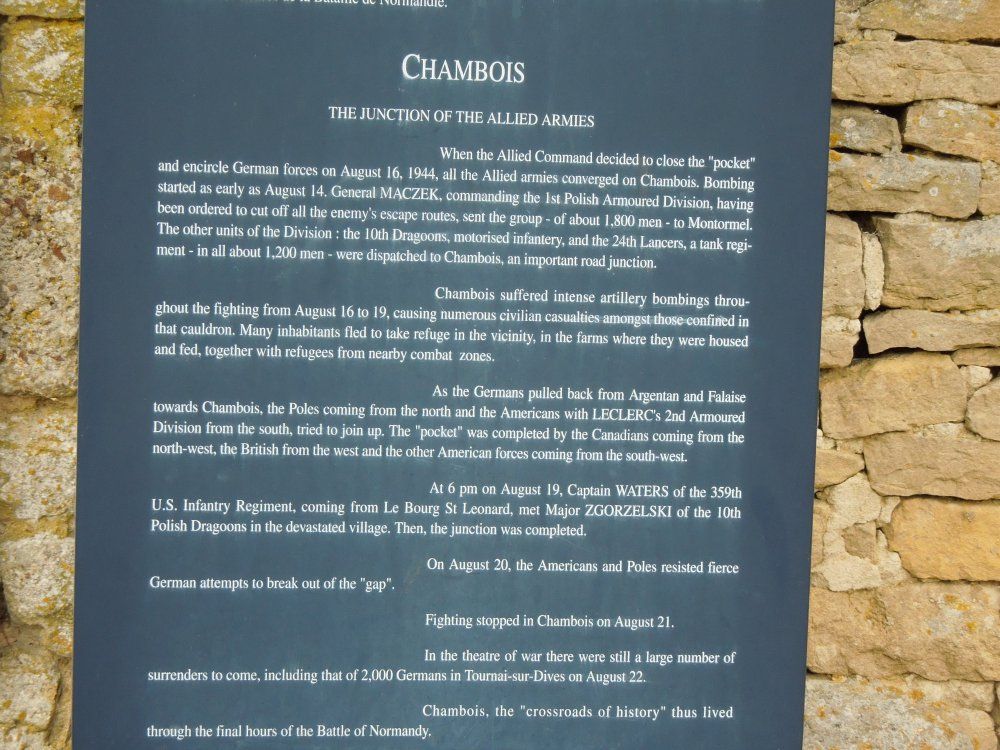

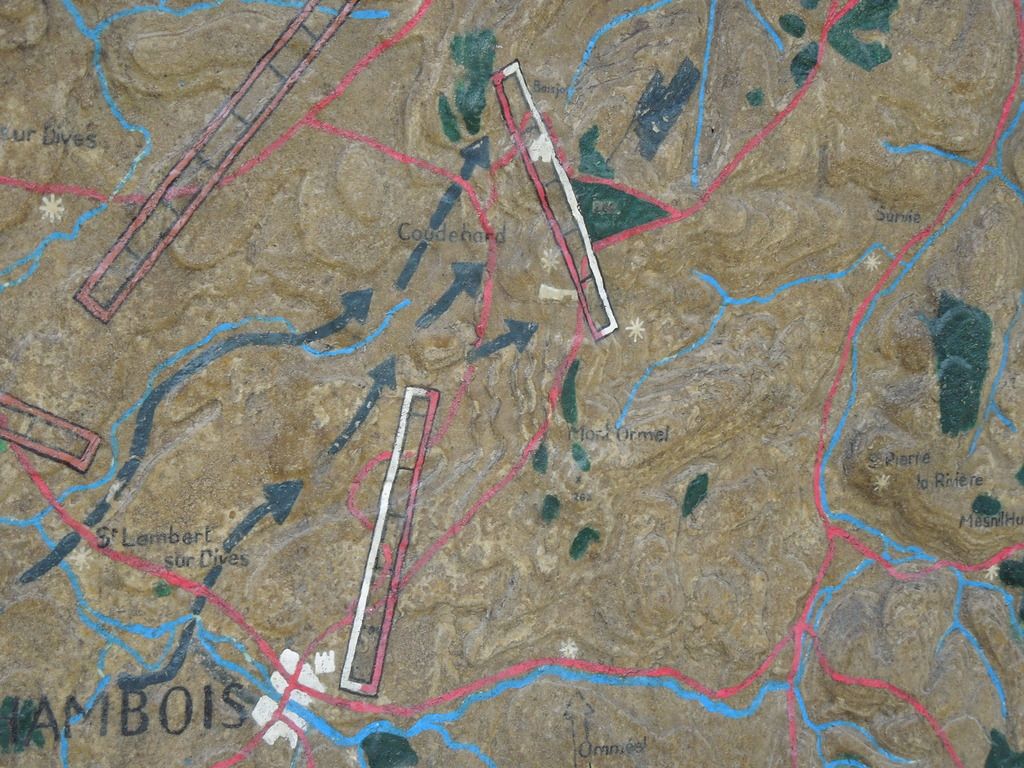

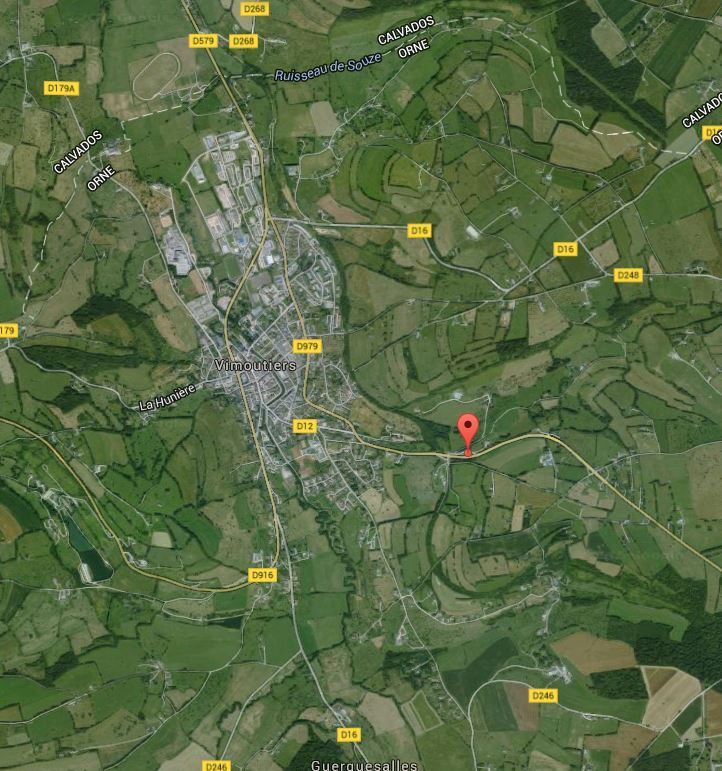

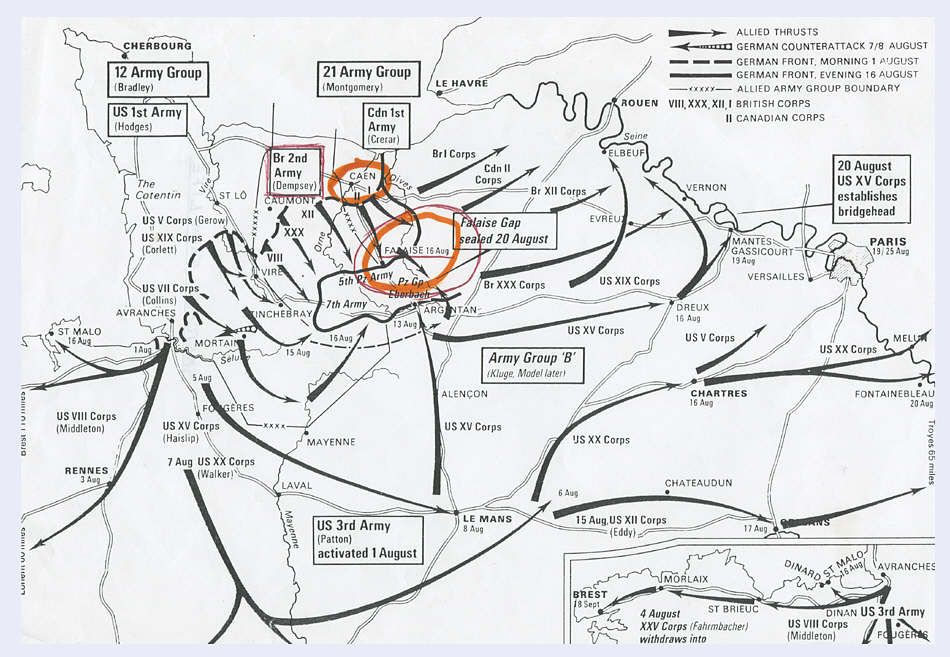

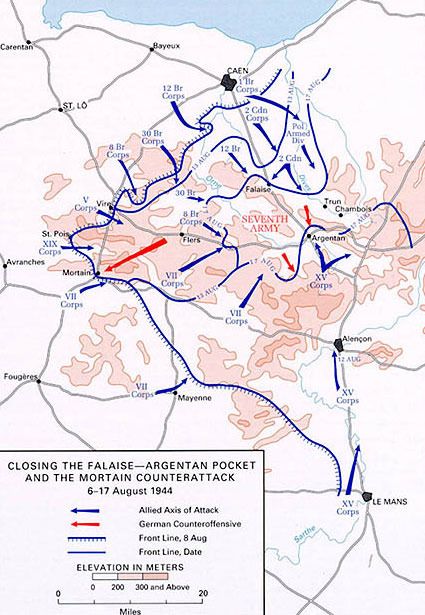

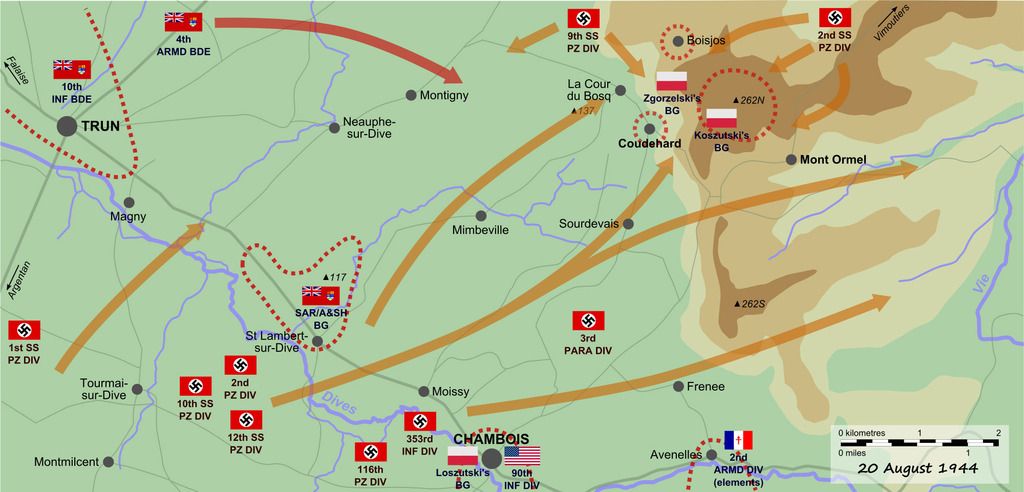

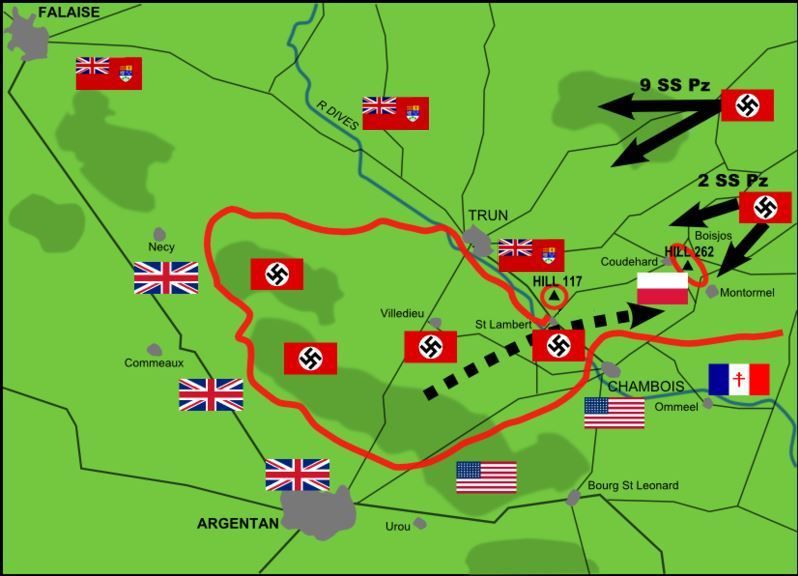

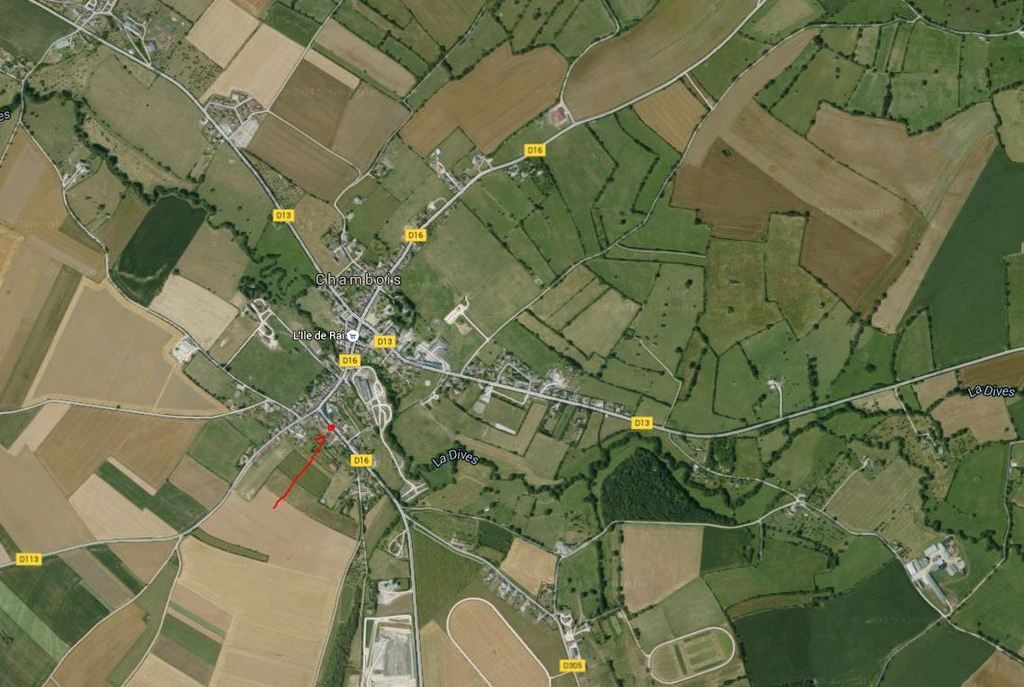

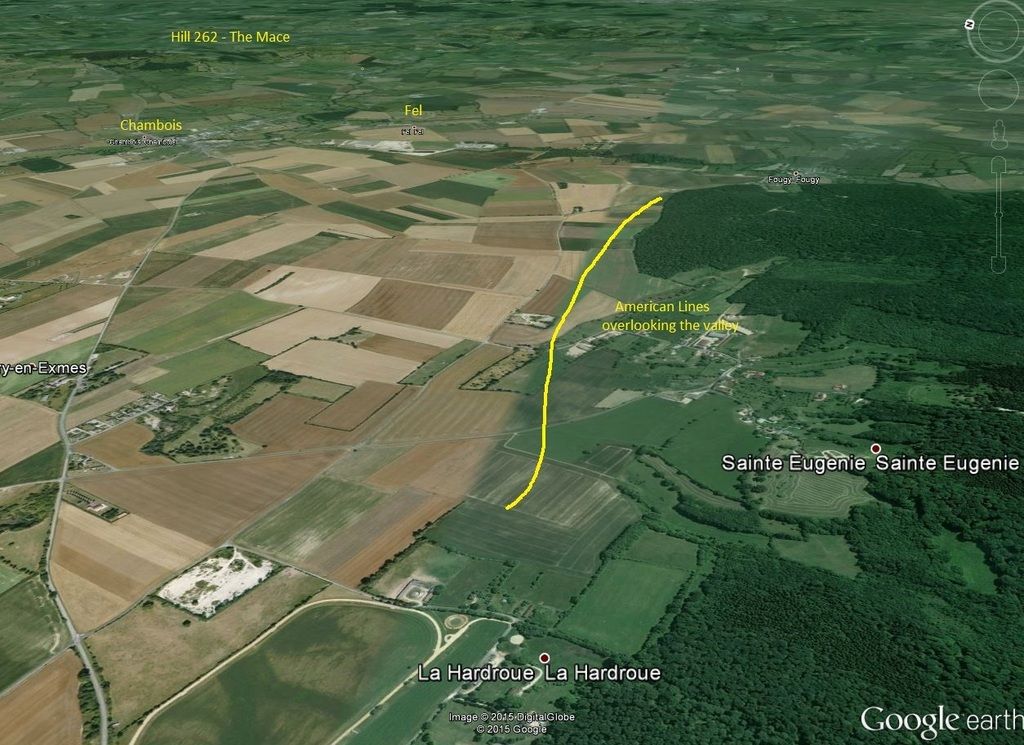

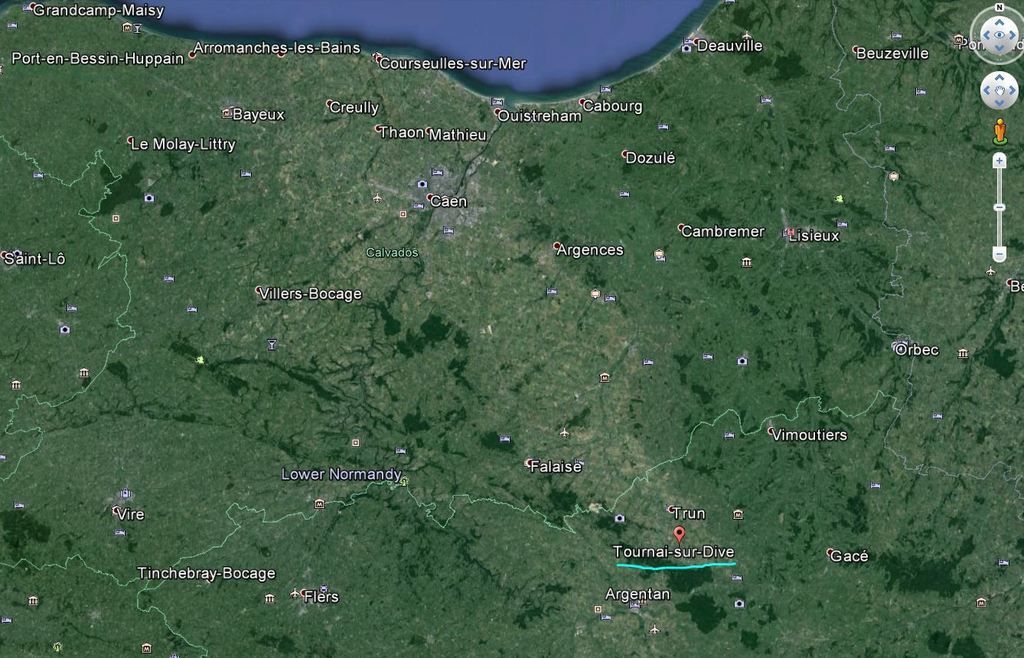

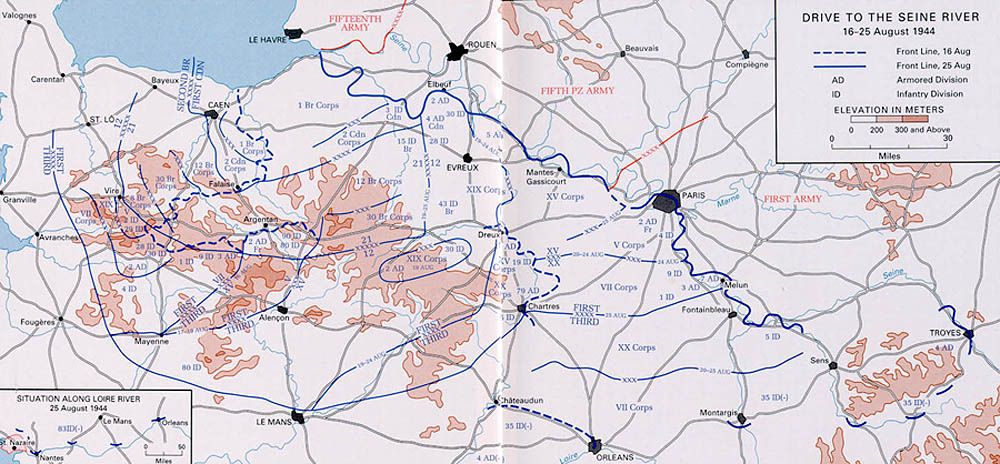

August 18th, Major Zgorzelski’s detachment pressed on towards Chambois, skirting to the north of Trun. However, General Maczek sought to take the high ground of Coudehard ï€ Mont-Ormel (262 m.), which commanded the plain and the valley of the Dives(s), where the Germans were still fighting savagely. Major Stefanowicz advanced on Hill 262 and was getting ready to occupy the whole of the crest when he found himself in the presence of the entire German army in full flight, using the Chambois-Vimoutiers road to escape from the encirclement. This road was, in point of fact, their last exit since, with the Americans holding Chambois, it was no longer possible to flee towards Gacé.

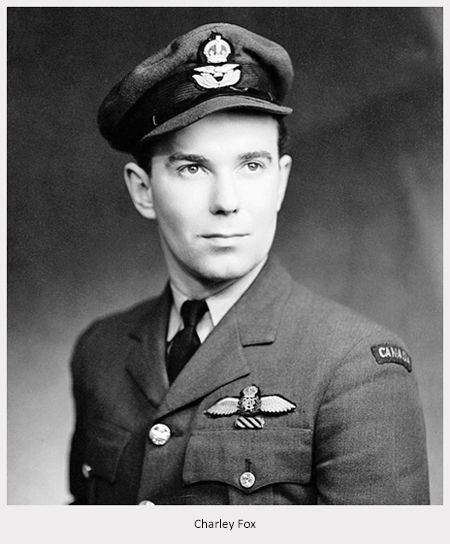

Polish General Stanislaw Maczek

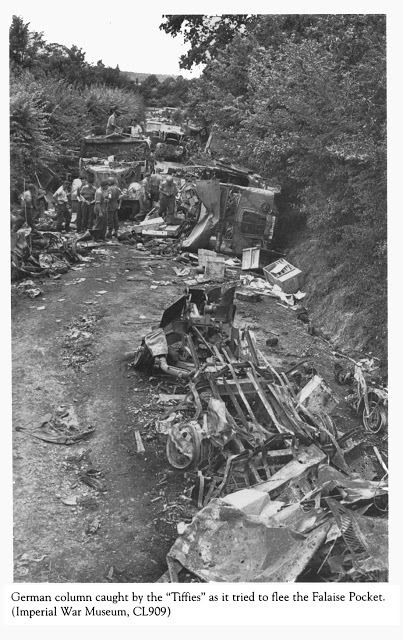

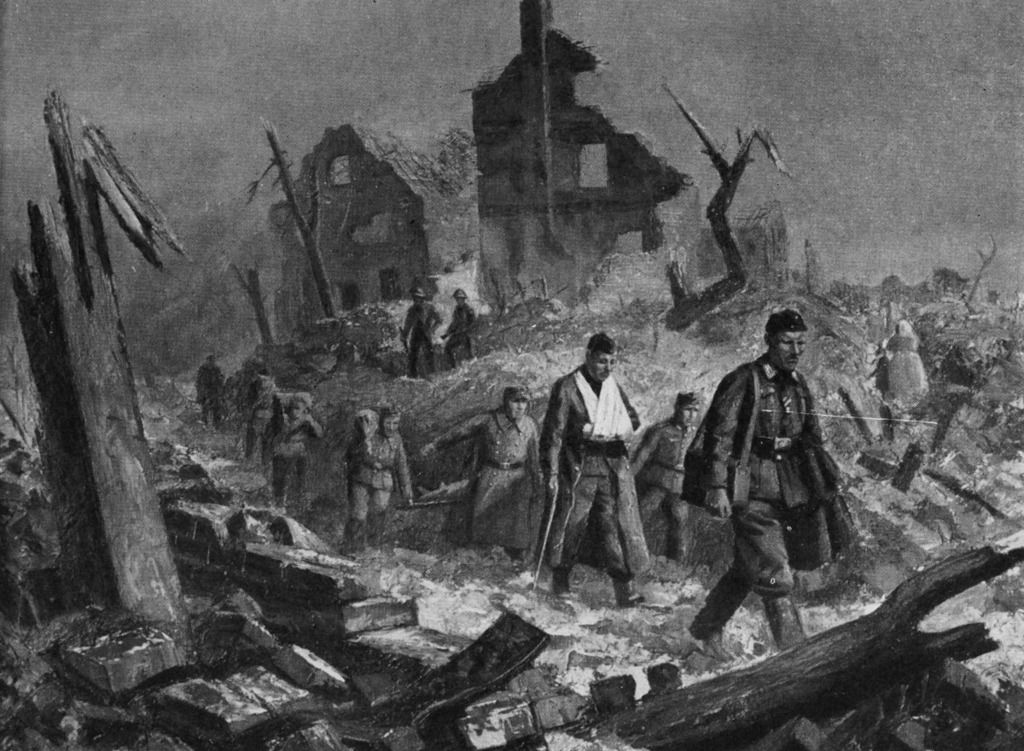

The Poles moved their tanks into position…, and commenced the massacre. The German columns came to a standstill under the persistent Polish fire. In panic men abandoned their equipment, setting fire to whatever would burn, cars, tanks and other vehicles. Then they took to their legs to save themselves. The bodies of men and horses strewed the road. When night came, the smoke of burning war material was so dense and impenetrable that visibility was reduced to nil and our Polish allies could advance no further.

On the 19th of August Lieutenant-Colonel Koszutski’s group, reinforced by the 9th Battalion of the Light Infantry, arrived on Hill 262. On the night of August 19th/20th, therefore, two armoured regiments and three battalions of light infantry held this strategic position. It was to be a terrible night.

The Germans were completely surrounded and hemmed in on the plain. They had no option but to attack at this point, apparently the most vulnerable in the containing ring. The tanks were in action for more than seventy hours; the fire was ceaseless, the terrain was crawling with men slipping stealthily along the hedgerows. At dawn, German armoured cars from St-Lambert burst through: S.S. troopers, trapped in 'the pocket' which was becoming a hellish cauldron, assaulted Hill 262 in waves. Their ferocious attacks pinned down the Polish units which were unable to close the whole width of the breach.

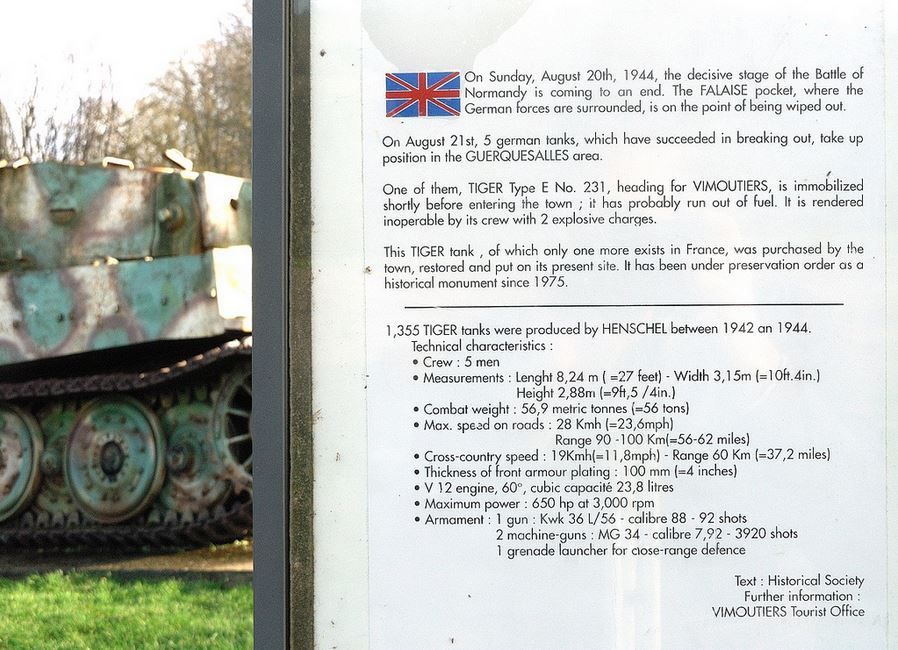

It was then that 2nd S.S. Panzer Corps, which had reached Vimoutiers the previous day after fighting its way out of the cauldron, received the order to move off and attack the Poles from the rear. Some Panthers, in a surprise attack, broke through the Polish perimeter and in a few minutes five tanks of the 1st Polish Armoured Regiment were set ablaze while their exhausted crews were still asleep. Supporting the Panthers were battalions of panzer grenadiers. The surprise was complete. There was an indescribable mêlée with vicious hand-to-hand fighting.

The element of surprise, the fatigue of the defenders, the Panther’s superiority over the Sherman and the lack of supplies created a situation such that the outcome of the battle depended on the valour of the men, their will to resist, and their determination to overcome the enemy, or be killed where they fought. Not one man fled! Not one surrendered!

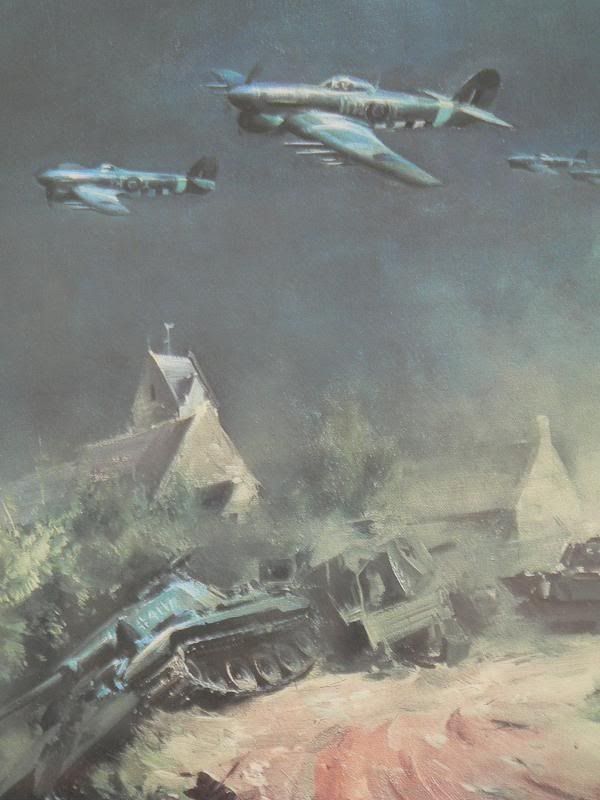

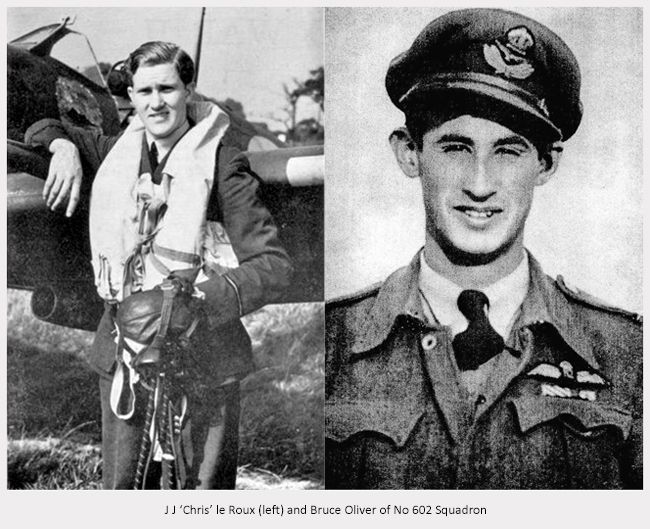

Hard pressed our Poles requested air support: impossible! They were told that in the mêlée the aircrew could not tell friend from foe, the air forces were to concentrate on the approach roads.

What follows is the account of Colonel Pierre Sévigny, a Canadian, then an artillery observation officer with the rank of Captain, attached to the 1st Polish Armoured Division. At the time of the attack on Saturday, August 19th, he had just joined his brave comrades in a regiment of armoured cavalry.

“At dawn the Polish major asked me to accompany a regiment of armoured cavalry which was about to support the attack on Hill 262 (Boisjos), the capture of which constituted our essential objective. A column of tanks set off for the attack. My vehicle was a Sherman tank armed with a cannon and two machine-guns. I had, in addition, two radio sets: one was for sending fire orders to my batteries which were to the rear; the other was to enable me to communicate with the front-line troops… We soon had the hill in sight: we found ourselves in the middle of hell. A company of German infantry, determined to hold it at no matter what cost, defended the position. Our troops had to annihilate them utterly; not one man would surrender. After several hours of desperate fighting the ground was finally ours: then I was able to observe the scene. The hill, 262 metres in height, was topped by a small wood near which was the old manor house (of Boisjos), half destroyed. The Germans had already dug a considerable network of trenches on its sides…. Enormous stocks of munitions were stored in every possible shelter…. This hill appeared to be essential to the enemy if he were to keep free the only two roads remaining to him.

The remains of a Polish Sherman tank and two German vehicles (a Panther tank and Sd.Kfz. 251 halftrack), destroyed in the vicinity of Boisjois near Point 262N

I could see clearly the two roads in question: the fire of the brigade’s guns would quickly have destroyed any enemy column attempting to pass through. The situation, thus, was favourable enough as far as it went. But…. the Canadians and Americans were showing no signs of life and the morning’s attack had cost us half of our effective strength! In addition, we had had no food for twenty-four hours; we were short of water; and an 88 had killed the doctor and destroyed all the medical supplies!

About three in the afternoon a patrol reported that two German columns were coming up towards us. That was the worst possible news! It meant the severing of our communications with the rear and the complete isolation of our group! Finally the enemy line of approach converged: I gave the order to aim at the crossroads. The batteries were ready, we waited! Fifteen minutes went by…. Utterly and completely motionless…. camouflaged, the troops lay in wait. The two columns reached the crossroads at exactly the same time. As we had foreseen there was confusion, everyone trying to move on to the road together: huge trucks filled with troops, guns drawn by six-horse teams, staff cars, reconnaissance half-tracks and even two enormous assault guns, armed with 88s. The disorder was total! Then, in a voice which I was trying to keep calm, I gave the order: “Fire!†Sixteen guns opened up simultaneously: twenty salvos were fired. Their 100 lb. shells fell on the heaving mass. What a massacre! The gun-layers did their work beautifully! I saw numerous vehicles burst into flames, terrified horses trapped in their harnesses. Men trying to flee….

Their efforts were in vain, a shell soon found them and I saw bodies flying through the air. Another shell lifted the turret from a tank; a tank nearby caught fire. Our machine-guns carried on the slaughter…. Ten minutes later everything on the road was in flames. Ammunition exploded inside the vehicles, killing the occupants.…

On our side we were unscathed! We had, however, to prepare for the counter-attack. Encouraged by this first success we quickly made Hill 262 into a fortified castle. Towards 17.00 we received a discouraging message: the Canadians were at a dead stop five miles away. In spite of all their efforts they could make no further progress without reinforcements. Our only hope hung on the Americans who were coming up from the south; they had to join us during the night. At 21.00 came another message: the Americans, too, had been stopped. Here we were then, by ourselves and completely surrounded!

The Polish major called his officers together and spoke to them all in French, for my benefit:

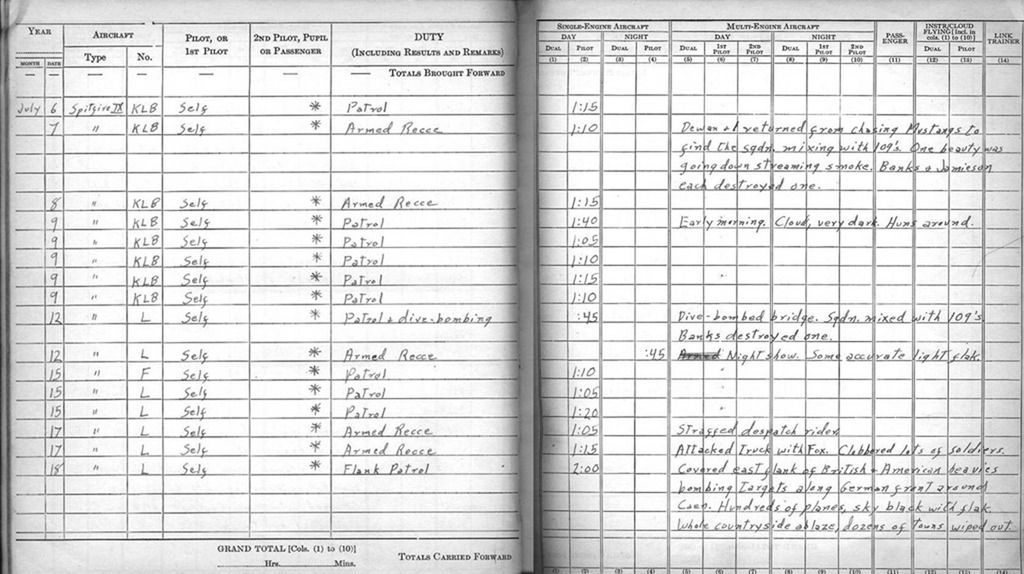

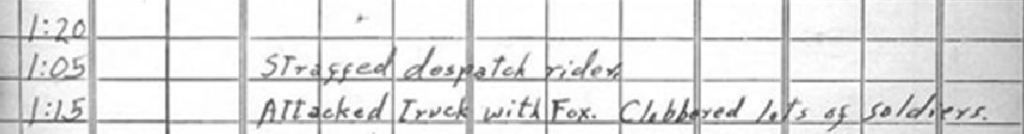

“Gentlemen,†he said, “the hour is grave. The brigade is completely isolated. The enemy is still fighting: his only escape routes are those you see to the right and to the left. There is nobody except us who can stop them: that is what we shall try to do! Surrender is out of the question! As Poles! This is what I propose to do: the infantry will hold the lower ground and will withdraw to the higher ground only in the last resort, the tanks will remain here in the little wood with engines stopped to save petrol. My Command Post will be in this old house where we are now (Boisjos Manor House).â€

Addressing me, he asked: “Can you lay down fire from your guns right round the hill?â€

I replied in the affirmative. Everybody shook hands and we went to our posts. I zeroed in my guns on four points where I expected enemy attacks. That way they would later be able to fire with accuracy whenever they were wanted.

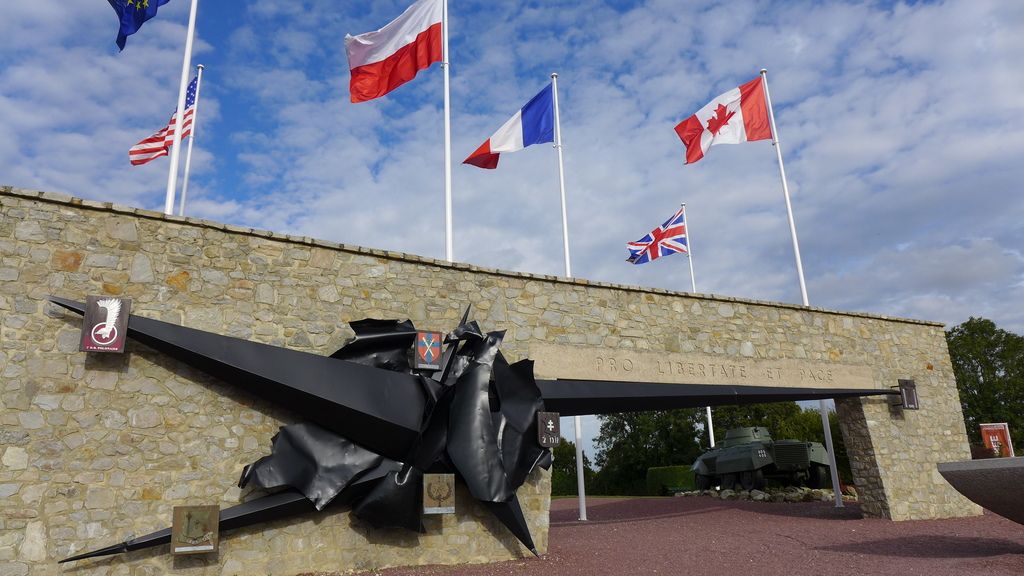

(Polish 1st Armored Division)

The night began. The men were calm. They did not know how grave the situation was. About midnight there was firing near the crossroads we had already shelled. Once again I gave the order: “Five rounds per gun!†We heard explosions and the cries of the wounded. However, firing broke on the left, then on the right. The enemy was attacking everywhere at the same time. At the foot of Coudehard hill there was bloody, hand-to-hand fighting all night. We lost many men and all we had for the wounded was a little iodine.

Sunday, August the 20th

Daylight came: it was absolutely essential for us to reorganise and contract our defence perimeter. All attacks had been repulsed but our losses during the night had been considerable. And it was still going on! Fortunately our dominating position ensured that we could not be surprised…! We fired without ceasing, the machine-guns and rifles grew red hot!

In the end the enemy pulled back but he still threatened the right. Attention! He was about to pass the first two points I had pre-ranged. I quickly gave the order to my signaller. The shells fell, the Boches were thrown back in disorder!

A lull. We were not short of things to trouble us: the major had been hit in the chest by a shell splinter. We had exhausted our rations, there was scarcely half a bottle of water left per man; ammunition was scarce! Suddenly, over on our left, we heard the sounds of numerous tanks moving! The Canadians! At last! We looked for the green flares. Nothing! We came down to earth: they were German tanks advancing on us.

The major then decided on a bold manoeuvre. The best defence was still attack: and we set off to meet the enemy with twelve tanks! We soon saw the silhouettes of sixteen, enormous, German tanks, Tigers! The battle began and within three minutes of the start we had lost six tanks to one of theirs!

Only the artillery could save us! Crouching in a hole I used a portable radio to send orders to my signaller to relay to the guns. And I waited: had I studied my map thoroughly enough? Had I marked the targets well enough? Would the guns fire in time? The steel monsters were still coming, firing with all their weapons. I saw the sparkling of their machine-guns: their 88s whistled over my head. What were our gunners doing? The leading tank was only 500 metres away…, 400 now, 300, 250, 200! It was all over! I no longer dared look! Yet, I looked again: 150 metres, 100 metres. I dived into the bottom of the hole, pressing my face to the earth, not daring to move. Death would come to me in seconds, of that I was sure…. Instinctively, I murmured a prayer…. Then, suddenly, a hurricane, rolls of thunder, the ground trembling! Death? Life? Could it be possible? Was this help? Our guns were firing! What I was hearing were our shells! And there, in the hole, I laughed and cried! Stupidly I raised my head, but only for an instant! We were saved! With unparalleled accuracy and at a prodigious rate of fire, unknown till then, a cloud of shells burst over the enemy.

The Boche hesitated. Five tanks were burning like haystacks. My gunners had orders to fire all their ammunition! The attack was broken: the Germans retired, pursued by the Poles who destroyed another three tanks! How I congratulated my men on the fine work they had done!

…….. Nevertheless the attack was soon renewed. Our losses mounted constantly…. but now I could not believe my eyes: the Boches were advancing towards us singing, “Deutschland, Deutschland über allesâ€! We let them come to within 50 yards, then we mowed down their ranks…. More waves followed.... When the fifth came we were out of ammunition. The Poles charged them with the bayonet! During that day we suffered eight attacks like this! The enemy was exploiting our weakness, but what fanaticism he showed! One of the wounded near me looked like a child: I read the date of birth in his paybook: April, 1931! He was thirteen years old. How horrible!

We took prisoners. Some of those from the Wehrmacht were of Polish birth. They were asked if they would join us: anyone who accepted was given the rifle and paybook of one of the dead! They were unexpected, precious reinforcements. The S.S. and those whose paybooks showed that they had taken part in the invasion of Poland in ’39 received no mercy!

About 6 o' clock the attacks ceased. The battlefield was a scene from a nightmare! On the flanks of the hill thousands of corpses made a veritable rampart. We had been forced back to the top of Hill 262. Around the wood, which was about 600 metres long and 300 metres across, now filled with the wounded, we had dug trenches which were to be held at all cost! Aircraft tried to drop supplies to us but all the containers fell behind enemy lines.

At nightfall that Sunday evening the major called his officers together: out of sixty only four were fit to fight, three lieutenants and myself, all the others, including the major himself, were more or less seriously wounded. Lying in terrible pain on some straw, the Polish major found the strength to pull himself upright and give his instructions. I will never forget his words:

“Gentleman, all is lost. I do not think the Canadians can relieve us. We have no more than 110 fit men. There is no food and not much ammunition: five shells per gun and fifty rounds per man! That is very little…. even so, fight on! It would be useless to surrender to the S.S., you know that! I give you my thanks: you have fought well. Good luck, gentleman, this night we will be dying for Poland and civilisation!â€

As he gave me his orders he added,

“Carry on with the same tactics. Afterwards it will be every tank for itself and then every man for himself!â€

By now very weak he stopped speaking…. When I got back to my tank the silence was like that of death. Suddenly, in the distance, I heard the rumble of tanks. This time there could be no mistake: these were Shermans, but they were still far off!

Now that communication with the Polish major had become pointless I tried to find some music on one of the radios. I tuned in to a German announcing, in perfect English, the encirclement of an entire Polish division in the Falaise area! He was exaggerating, but he was not exactly lying! I tuned to another station: Strauss waltzes, played by an orchestra in London: I could hear the voices and laughter of the dancers. Over there, a different world was taking its pleasure!

In Canada the theatres in every town would be overflowing with people. I thought of the days when I knew nothing of war…. I thought of my parents…. so anxious at hearing that I was on the continent…. feelings shared by thousands of families throughout the world who prayed for only one thing: that God would protect their sons in the fire of battle.... Now it was finished: in the last forty-eight hours thousands of men had been wiped out before my eyes…. It would soon be my turn!

I was thinking for a long time, and the night went by.

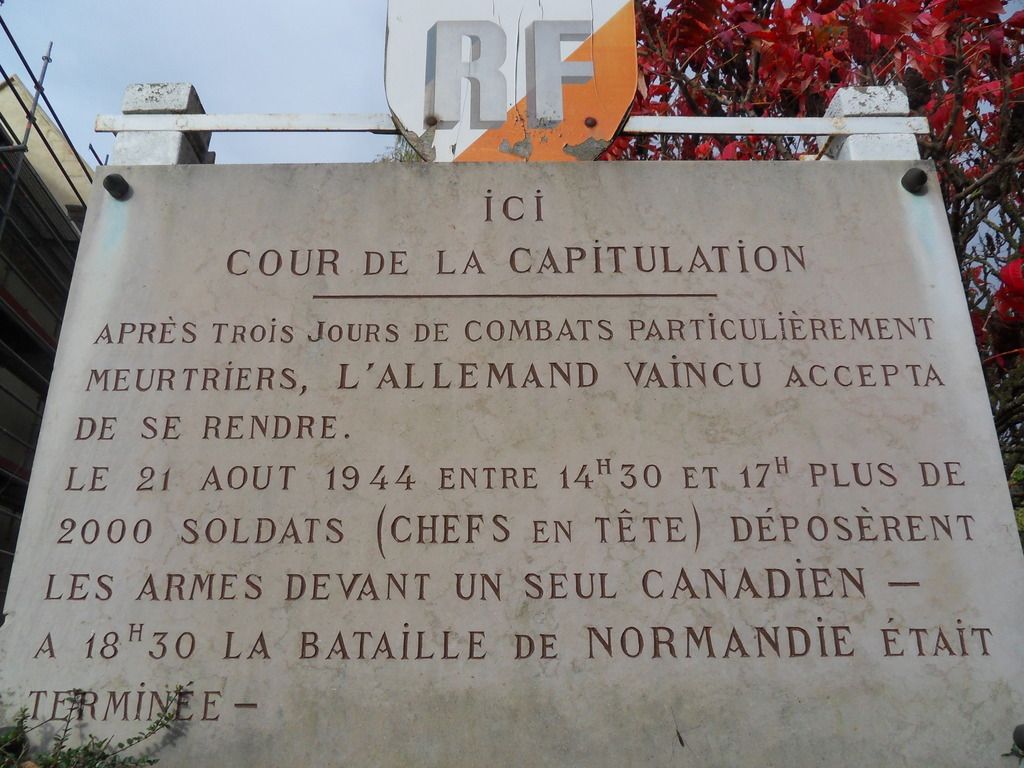

Nearly 4 in the morning, Monday, August the 21st

A shaft of moonlight lit the clearing in front of me: shadows! Immediately came a burst of machine-gun fire. A quarter of an hour later, a new attack! We were losing a lot of men, among them two of the Polish lieutenants: there was only one left!

Half an hour later it was dawn. I went to sleep literally standing up. Suddenly my signaller woke me and I started: “Captain, I can hear our tanks!â€

There was no possible mistake! They must have been very close, perhaps 600 metres to the west, and I could clearly distinguish the two, green flares. Between them and us, however, on the side of the hill lay a small, thick wood and the Germans were still in it. What were we to do? If our friends bumped into resistance the likelihood was that they would pull back and look for another way. No hesitation! We had to attack and link up with our relief no matter what it cost.

Immediately I gathered the men. They all agreed: we had to take the enemy by surprise. Luckily his attention was diverted by the noise of the tanks! At the blast of a whistle we went forward! We advanced quickly despite branches, craters and the S.S. Nothing could stop the wrath of the Poles. The Polish lieutenant was in front of me: I saw him fall, hit in the forehead by a bullet. At the same time, from behind a tree, a soldier aimed his carbine at me: I threw myself to one side as he fired: he missed and was instantly bayoneted. A bullet grazed my left shoulder: it was nothing, and we reached the bottom of the hill to see six Shermans firing on us! They finally recognised us and, with our strength increased, we were soon climbing back up that famous Hill 262.

When we reached the Command Post the Polish major greeted us, he was shaking with emotion and I became part of a scene of delirious joy. We laughed, we wept, we embraced each other. The soldiers told long stories in Polish to the Canadians who understood not a word but nevertheless burst into peals of laughter!

Our victory was total, but at a terrible price: only seventy Poles survived the slaughter unhurt: I was the only officer still able to stand!

(Polish soldiers resting next to a Sherman after the battle)

The Poles now call that hill “Maczugaâ€, which means “The Maceâ€. And that is it exactly: the battle of “Maczuga†hill was the final, crushing blow which broke German power."

(Pierre SEVIGNY, Montréal)

The Balance-sheet of this fearful confrontation:

The Poles, who went into this fight with eighty-seven Sherman tanks against all the remaining weaponry of the German Seventh army surrounded on the plain of Tournai ï€ Aubry ï€ St-Lambert, lost 325 dead, 16 of whom were officers, 1,002 wounded and 114 missing. Eleven tanks were destroyed.

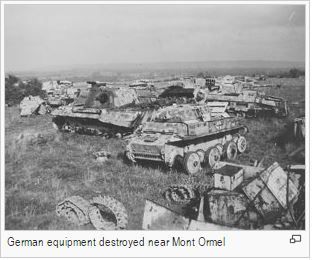

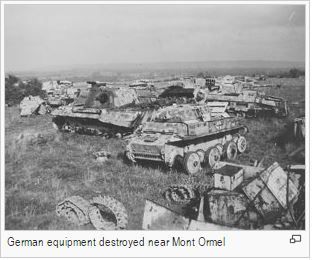

The Germans had about 2,000 killed, 5,000 taken prisoner, including a general, six colonels and 80 officers. They left on the battlefield 55 tanks, of which 14 were Panthers and 6 Tigers, 44 guns and 152 armoured vehicles, 359 vehicles of all types were destroyed.